When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure it actually does? The answer lies in bioequivalence-a strict scientific standard that bridges the gap between brand-name drugs and their cheaper copies. This isn’t about matching ingredients by weight. It’s about proving that your body absorbs and uses the generic drug in the same way as the original.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t a vague promise. It’s a measurable outcome defined by the FDA as the absence of a significant difference in how fast and how much of the active drug enters your bloodstream compared to the brand-name version. The key words here are rate and extent. That means the generic must deliver the same amount of medicine, at roughly the same speed, to the same place in your body.

Think of it like pouring two different brands of soda into identical glasses. You don’t just check if they have the same sugar content-you measure how quickly the fizz rises and how much liquid ends up in the glass. If both are nearly identical, you can trust they’ll taste the same. That’s bioequivalence.

The Science Behind the Numbers

To prove bioequivalence, manufacturers run clinical studies with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These are crossover trials, meaning each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, at different times, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken over hours to track how the drug moves through the body.

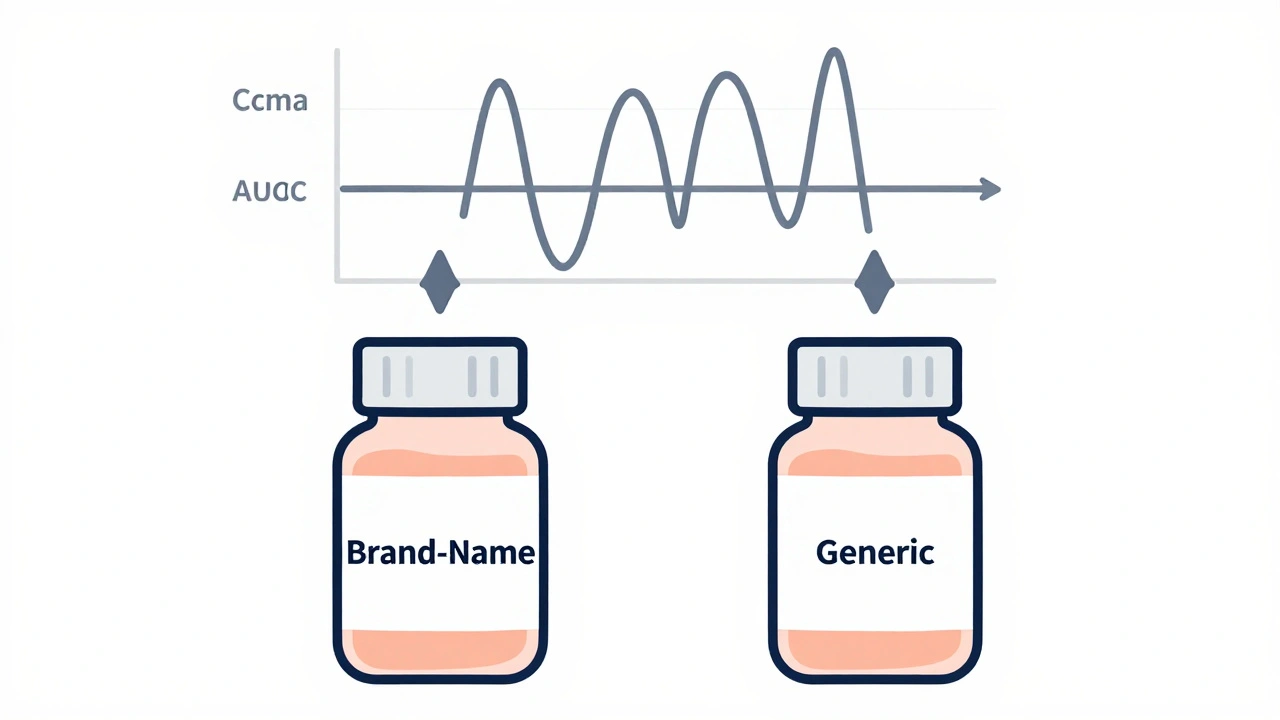

Two numbers matter most:

- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast it’s absorbed.

- AUC: The total exposure over time-how much of the drug your body actually gets. AUC(0-t) covers the time until the last measurable level; AUC(0-∞) estimates the full exposure, even beyond what’s measured.

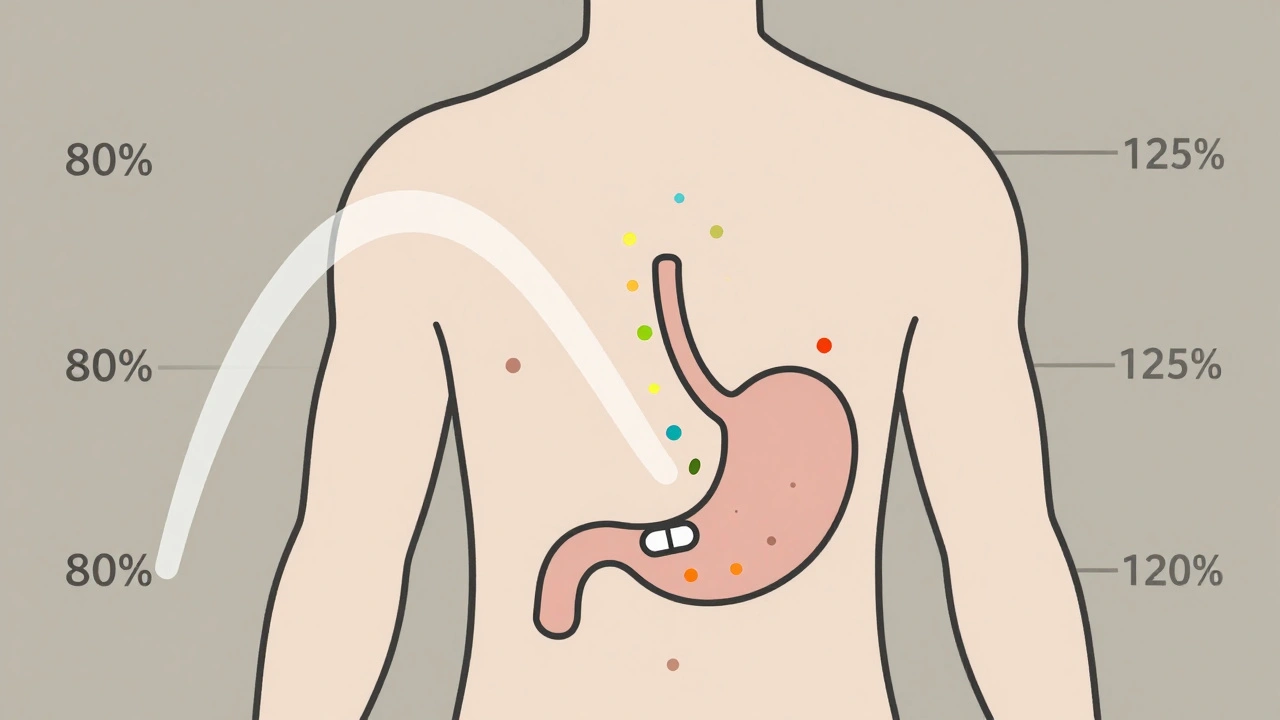

The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval of the ratio (generic / brand) for both Cmax and AUC falls between 80% and 125%. That’s not a range for how much active ingredient is in the pill. It’s a range for how your body handles it.

For example: If the brand-name drug gives an average AUC of 100 units, the generic must produce an AUC between 80 and 125 units. If the generic’s average is 93, and the 90% confidence interval runs from 84 to 110, it passes. But if the average is 116 and the interval stretches to 130, it fails-even though the average is within range, the upper limit exceeds 125%.

Why the 80-125% Rule Isn’t as Loose as It Sounds

A common myth is that generic drugs can contain anywhere from 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The active ingredient in a generic pill must be identical in amount to the brand-name drug. The 80-125% range applies only to how your body absorbs and uses it-not what’s inside the tablet.

The FDA picked this range because research shows a 20% difference in absorption is clinically insignificant for most drugs. If a drug’s effect changes by less than 20% in blood levels, it’s not going to cause harm or reduce effectiveness in real-world use. This isn’t arbitrary-it’s based on decades of clinical data and statistical modeling.

Pharmaceutical Equivalence Comes First

Bioequivalence can’t be proven unless the generic is also pharmaceutically equivalent. That means:

- Same active ingredient

- Same strength

- Same dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection)

- Same route of administration (oral, topical, etc.)

- Same quality standards

So even if two pills have identical active ingredients, if one is a slow-release tablet and the other is immediate-release, they’re not considered equivalent. The FDA won’t even test for bioequivalence unless all these boxes are checked.

When the Rules Change: Complex Drugs and Special Cases

Not all drugs follow the same rules. For drugs that act locally-like inhalers, creams, or eye drops-the FDA may allow in vitro testing instead of human trials. If the drug doesn’t need to enter the bloodstream to work, measuring how it dissolves or spreads in a lab can be enough.

But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where even small changes can cause toxicity or treatment failure-the stakes are higher. Think warfarin, lithium, or certain epilepsy drugs. The FDA still uses the 80-125% range, but manufacturers are expected to provide stronger evidence. Some experts argue tighter limits should apply, but the FDA maintains the standard works across most cases when studies are well-designed.

The Approval Process: ANDAs and Transparency

Generic manufacturers don’t submit new clinical trials proving safety and efficacy. Instead, they file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This skips the expensive animal and human trials already done by the brand-name company. But they must prove bioequivalence-and now, they have to submit all studies they ran, not just the successful ones.

Since 2021, the FDA requires full transparency. If a company ran five bioequivalence studies and only one passed, they still have to report the other four. This prevents cherry-picking and helps the FDA spot patterns-like a formulation that only works under ideal conditions.

On average, the FDA reviews about 1,000 ANDAs each year. About 65% get approved on the first try. The rest get deficiency letters-often because the dissolution profile didn’t match, or the bioequivalence data had gaps. Common fixes? Reformulating the pill, changing the manufacturing process, or adjusting the test design.

Why This Matters: Cost, Access, and Trust

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they cost only about 20% of what brand-name drugs do. Over the last decade, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.7 trillion. Without bioequivalence standards, that savings wouldn’t be possible-or safe.

Patients trust generics because they know the FDA has verified they work the same way. That trust isn’t built on marketing. It’s built on data, controlled studies, and strict rules. Even when a generic looks different-color, shape, or name-it’s not a different drug. It’s the same medicine, proven to behave the same way in your body.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The FDA is exploring new ways to make bioequivalence testing faster and smarter. Modeling and simulation tools are being tested to predict how a drug will behave without running full human trials-especially for complex products like topical creams or injectables.

By 2025, more complex generics are expected to hit the market as these new methods become standard. The goal isn’t to lower standards-it’s to apply them more efficiently. Whether it’s a simple tablet or a complicated inhaler, the rule stays the same: if your body doesn’t handle it the same way, it’s not equivalent.

Do generic drugs contain less active ingredient than brand-name drugs?

No. Generic drugs must contain the exact same amount of active ingredient as the brand-name version. The 80-125% range applies to how your body absorbs the drug (measured by Cmax and AUC), not the amount of drug in the pill. The FDA requires pharmaceutical equivalence first-meaning identical strength, dosage form, and active ingredient content.

Why do some people say generic drugs don’t work as well?

Most of the time, this comes from placebo effects or differences in inactive ingredients-like fillers or coatings-that change how a pill looks or tastes. The active drug is the same. In rare cases, a patient might be sensitive to a non-active ingredient, but that’s not a bioequivalence issue. The FDA’s standards ensure the medicine works the same way in your bloodstream. If you feel a difference, talk to your doctor, but it’s unlikely the generic is failing the bioequivalence test.

Are all generic drugs approved the same way?

No. The FDA uses product-specific guidances for over 2,000 drugs. For simple oral tablets, in vivo bioequivalence studies with healthy volunteers are standard. For drugs that act locally-like nasal sprays or topical creams-the agency may accept in vitro testing. For complex drugs like biologics or extended-release formulations, additional data or specialized studies are required. Each drug has its own path to approval.

Can a generic drug be approved even if its bioequivalence study fails?

No. The FDA requires at least one successful bioequivalence study to approve a generic. However, since 2021, manufacturers must submit all studies they conducted-even the failed ones. This helps the FDA understand why a formulation didn’t work and whether it can be fixed. A failed study doesn’t mean the drug is unsafe, but it does mean the manufacturer must reformulate or redesign before resubmitting.

How long does it take for the FDA to approve a generic drug?

The standard review time for an ANDA is 10 to 12 months. First-cycle approval rates are around 65%, meaning about one in three applications need revisions before approval. Delays usually come from incomplete data, mismatched dissolution profiles, or issues with bioequivalence study design. The process is faster if the manufacturer follows the FDA’s product-specific guidance closely.

Lynn Steiner

December 3, 2025 AT 07:05This is why I refuse to take generics. My cousin took some and ended up in the ER. Who the hell lets this stuff fly under the radar? 🤬

Jay Everett

December 3, 2025 AT 20:55Bro, the FDA’s 80-125% range isn’t a loophole-it’s a masterpiece of clinical math. Think of it like a thermostat: ±10% variance and your house still feels cozy. Same logic. Your body doesn’t care if the pill is blue or white-it cares if the drug hits the same target at the same pace. 🧠💊

Jack Dao

December 4, 2025 AT 10:44Oh please. You think the FDA is some saintly guardian of public health? They’re a regulatory circus. I’ve seen generics that look like they were made in a garage. And don’t get me started on the ‘bioequivalence’ studies-24 healthy volunteers? That’s not science, that’s a college project. 🤷♂️

Alicia Marks

December 5, 2025 AT 07:55It’s okay to be skeptical, but trust the data. Generics save lives and wallets. You’re not losing anything-just getting the same medicine without the brand markup. 💪

Elizabeth Grace

December 5, 2025 AT 14:17I used to hate generics until I switched to one for my anxiety med. Same effect, half the price. Honestly? I felt better because I wasn’t stressing about the cost. 😌

Steve Enck

December 6, 2025 AT 04:11The 80-125% confidence interval is statistically defensible only under the assumption of homoscedasticity and normal distribution of pharmacokinetic parameters. Yet, in real-world populations, inter-individual variability often violates these assumptions. The FDA’s adherence to this heuristic is not evidence-based-it is institutional inertia masquerading as regulatory rigor. 📊

मनोज कुमार

December 6, 2025 AT 05:14Roger Leiton

December 7, 2025 AT 09:03Wait so if a generic has the same active ingredient but different fillers, and I have a weird reaction to one of those, does that mean the FDA’s system still works? Like… it’s not the drug’s fault, it’s the filler? 🤔

Paul Keller

December 8, 2025 AT 06:23It’s fascinating how the FDA has managed to balance innovation, safety, and accessibility through this framework. The 80-125% range isn’t arbitrary-it’s derived from decades of pharmacokinetic modeling and clinical outcomes data. The fact that generics now account for 90% of prescriptions while maintaining therapeutic equivalence speaks volumes about the rigor of the system. It’s a triumph of regulatory science, not a compromise. And yes, the transparency mandate since 2021-that’s a game-changer. No more cherry-picking. Just raw data. That’s accountability.

What’s even more impressive is how they adapt. For topical drugs, in vitro testing replaces human trials. For narrow-therapeutic-index meds, they don’t lower the bar-they demand more data. That’s not laziness. That’s precision.

And let’s be real: if you feel different on a generic, it’s likely the placebo effect, or your brain is fixated on the color change. The active molecule doesn’t care if it’s called Lipitor or atorvastatin. It binds the same receptors. The body doesn’t read labels-it reads chemistry.

So when someone says ‘my generic didn’t work,’ ask them: did they measure the plasma concentration? Or are they just projecting their distrust onto a pill?

Generics aren’t cheap alternatives. They’re scientifically validated equivalents. And the system that ensures that? It’s one of the most brilliant public health achievements of the last century.

Laura Baur

December 8, 2025 AT 15:38Let’s be brutally honest: the entire bioequivalence framework is a beautiful illusion engineered to justify corporate profit margins under the guise of public health. The 80-125% range was chosen not because it’s biologically optimal, but because it’s the widest interval that still allows manufacturers to avoid costly reformulation. The FDA’s reliance on healthy young volunteers? That’s a glaring flaw. Most patients are elderly, diabetic, or on polypharmacy regimens. Their absorption profiles are wildly different. Yet we pretend a 24-year-old male’s pharmacokinetics represent a 72-year-old woman with renal impairment. This isn’t science-it’s systemic neglect dressed in lab coats. And don’t get me started on the fact that the FDA still approves generics with failed studies, as long as one passes. That’s not due diligence. That’s gambling with lives.

Meanwhile, the $1.7 trillion in savings? Sure. But at what cost? How many patients suffered subtherapeutic doses because their generic’s dissolution profile shifted under humidity? How many adverse events were buried because the FDA only reviews the ‘successful’ data? Transparency is a PR stunt. The real data? Still locked behind NDAs and proprietary formulations. We’re being sold a lie wrapped in statistical confidence intervals.

And yet, people cheer. They don’t question. They trust. That’s the real tragedy. Not the generics. Not the FDA. But our collective willingness to believe that a number on a chart is the same as safety.

Shannara Jenkins

December 9, 2025 AT 12:06Love how you broke this down! I used to think generics were sketchy too, but now I know it’s just science doing its job. 🙌 And honestly? My blood pressure med works better on the generic because I actually remember to take it now-it’s cheaper and I’m not stressed about the bill. You’re not losing quality-you’re gaining peace of mind. 💙

Joel Deang

December 9, 2025 AT 14:39bro the fda is legit. i switched to generic adderall and my focus is the same. the pill looks diff but the magic is in the chem. 🤘

Alicia Marks

December 10, 2025 AT 15:33Exactly. If it works for your anxiety, your blood pressure, your thyroid-why doubt it? The science is solid. Trust the data, not the color.