CKD Stage & Bone Risk Estimator

Enter your details to estimate your kidney function stage and understand associated bone health risks:

When your kidneys start to falter, the ripple effects reach far beyond just fluid balance - they can silently erode the strength of your skeleton. Understanding why bone loss often accompanies kidney problems helps patients and clinicians spot trouble early and take action before fractures become inevitable.

TL;DR

- Kidney disease disrupts calcium, phosphate, and hormone balances that are essential for healthy bones.

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can cause a specific bone disorder called renal osteodystrophy.

- Key biomarkers - PTH, vitamin D, FGF23, and serum phosphate - guide diagnosis and treatment.

- Managing diet, medication, and lifestyle can slow bone deterioration even in advanced CKD.

- Regular bone mineral density (BMD) testing is crucial for anyone on dialysis or with stage3+ CKD.

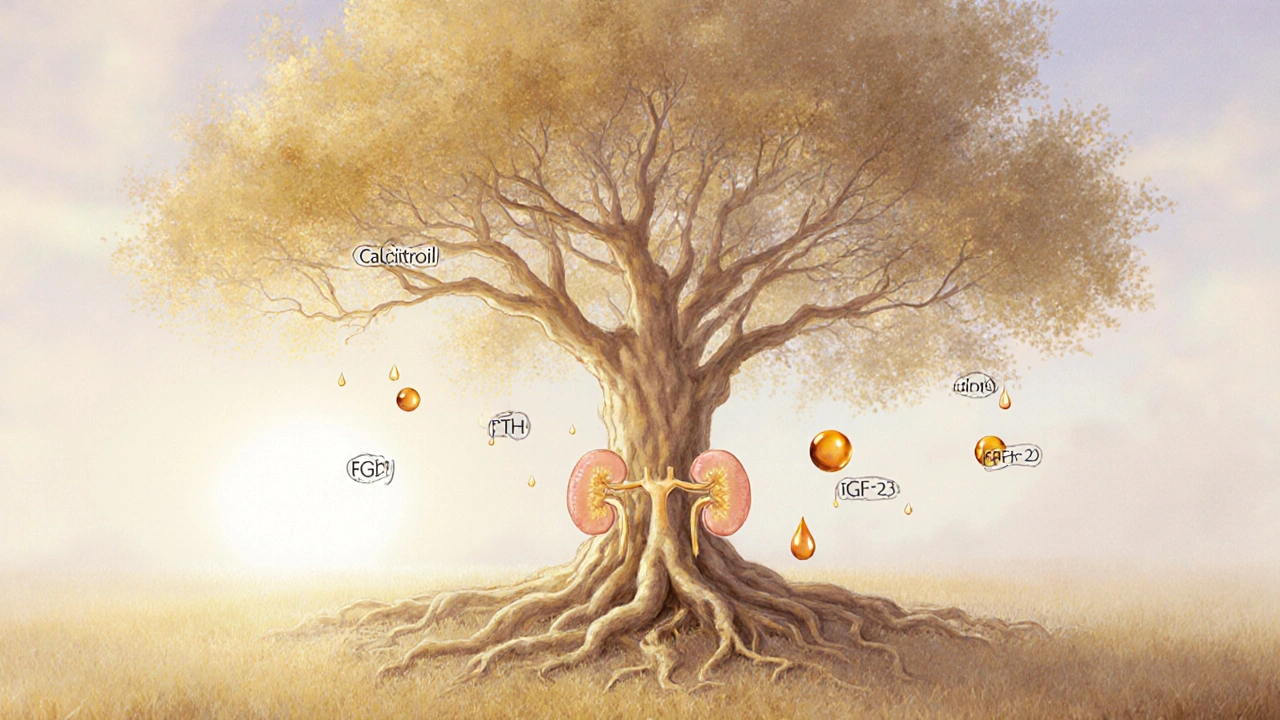

How Kidneys Keep Your Bones Strong

Kidney disease is a condition where the kidneys lose the ability to filter blood efficiently. One of the kidneys' lesser‑known jobs is to regulate minerals that build bone. They filter out excess phosphate is a mineral that, in high amounts, pulls calcium out of bone and convert inactive vitamin D is a fat‑soluble vitamin that boosts calcium absorption in the gut into its active form, calcitriol. When these processes falter, calcium and phosphate levels go haywire, and the endocrine system steps in.

Key Hormonal Players in the Bone‑Kidney Axis

The parathyroid glands secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a hormone that raises blood calcium by releasing it from bone, increasing gut absorption, and reducing renal excretion. In CKD, low active vitamin D and high serum phosphate trigger the glands to overproduce PTH - a state called secondary hyperparathyroidism. Over time, the relentless PTH surge leaches calcium from the skeleton, weakening trabecular and cortical bone.

Another culprit is fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is a hormone that signals kidneys to excrete phosphate and suppresses vitamin D activation. As kidney function declines, FGF23 levels sky‑rocket, further reducing active vitamin D and compounding phosphate retention. The combined effect accelerates bone turnover and loss.

Renal Osteodystrophy: The CKD‑Specific Bone Disorder

When bone disease in the context of CKD is clinically identified, it is termed renal osteodystrophy is a spectrum of bone pathologies caused by chronic kidney disease, including high‑turnover and low‑turnover lesions. Unlike primary osteoporosis, which mainly involves decreased bone mass due to age or estrogen loss, renal osteodystrophy can present as:

- High‑turnover bone disease (osteitis fibrosa) driven by excessive PTH.

- Low‑turnover bone disease (adynamic bone) often linked to over‑suppression of PTH by vitamin D analogs.

- Mixed lesions where both processes coexist.

Identifying the specific subtype is essential because treatment strategies differ markedly.

Assessing Bone Health in Kidney Patients

The first step is measuring the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is a test that estimates how much blood the kidneys filter each minute. A GFR below 60mL/min/1.73m² signals stage3 CKD, where bone complications often start to appear. Regular blood panels track calcium, phosphate, PTH, 25‑OH vitamin D, and FGF23.

Imaging also plays a role. Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans provide bone mineral density (BMD) is a measurement of bone strength expressed in grams per square centimeter, typically reported as T‑scores or Z‑scores. In dialysis patients, BMD scores below -2.5T indicate a high fracture risk.

Managing Bone Loss in Chronic Kidney Disease

Effective management hinges on three pillars: correcting mineral imbalances, modulating hormones, and supporting bone formation.

- Dietary control: Limit phosphate intake by avoiding processed meats, cola, and dairy substitutes high in phosphorus additives. Encourage calcium‑rich foods like leafy greens, but keep total calcium intake below 1,200mg/day unless prescribed supplements.

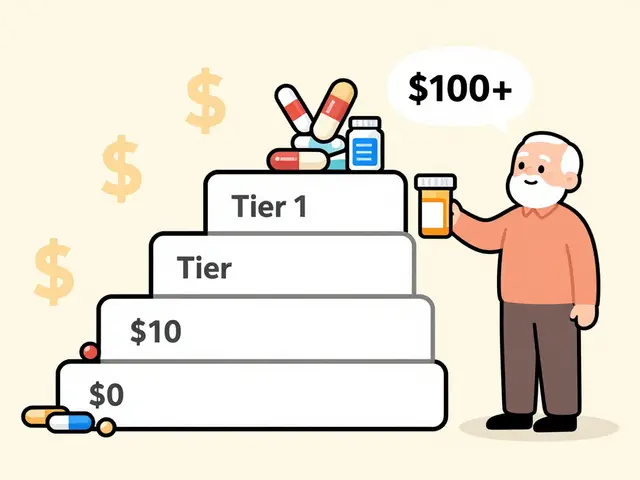

- Phosphate binders: Medications such as sevelamer or calcium acetate bind dietary phosphate in the gut, preventing absorption. Choice depends on serum calcium levels and vascular calcification risk.

- Active vitamin D analogs: Calcitriol or alfacalcidol raise calcium absorption and suppress PTH. Doses are titrated based on PTH trends and calcium levels.

- Calcimimetics: Drugs like cinacalcet increase the sensitivity of the parathyroid gland to calcium, lowering PTH without raising calcium.

- Bisphosphonates and denosumab: In selected CKD stage3‑4 patients, anti‑resorptive agents can be used, but they require caution in stage5 or on dialysis due to altered clearance.

Physical activity, especially weight‑bearing exercises such as brisk walking or resistance training, stimulates bone formation and improves balance, reducing fall risk.

When Kidney Disease Progresses to Dialysis: Bone Considerations

Patients on hemodialysis face the highest bone‑fracture rates. The dialysis process itself removes some phosphate, but not enough to normalize levels. Regular monitoring of PTH (target 2‑9 times the upper normal limit for the assay) guides therapy adjustments.

Emerging treatments target FGF23 pathways, but as of 2025 they remain investigational. Meanwhile, maintaining adequate nutrition, limiting acid‑load foods, and ensuring appropriate vitamin D dosing remain the mainstay.

Practical Tips for Patients and Caregivers

- Ask your nephrologist for a yearly DXA scan once you reach CKD stage3.

- Keep a food diary focused on phosphate additives - many packaged foods hide phosphate under names like "phosphoric acid" or "pyrophosphate".

- Stay active: 30 minutes of moderate exercise most days can boost BMD by up to 2% per year.

- Never self‑adjust supplements; excess calcium or vitamin D can worsen vascular calcification.

- Discuss fall‑prevention measures at home - grab bars, non‑slip mats, and proper lighting are simple but effective.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does kidney disease increase fracture risk?

Impaired kidneys disrupt calcium‑phosphate balance and elevate PTH and FGF23, leading to bone demineralization. Additionally, CKD patients often have muscle weakness, which raises fall risk.

Can osteoporosis drugs be used in dialysis patients?

Bisphosphonates are generally avoided after dialysis starts because they can accumulate and cause adynamic bone disease. Denosumab may be safer, but dosing must be individualized and calcium levels closely watched.

What blood tests indicate worsening bone health in CKD?

Rising PTH, high serum phosphate, low calcium, and dropping 25‑OH vitamin D are red flags. An upward trend in FGF23 also signals mineral dysregulation.

How often should a CKD patient get a DXA scan?

Guidelines suggest a baseline scan at CKD stage3, then every 1-2years if results are normal, or annually if T‑scores are below -2.0.

Is it safe to take calcium supplements while on phosphate binders?

Only if your serum calcium is low and you’re not already using calcium‑based binders. Over‑supplementation can cause vascular calcification, especially in advanced CKD.

Quick Reference Table

| Feature | CKD‑Related Bone Loss | Primary Osteoporosis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary driver | Mineral imbalance & hormonal dysregulation (PTH, FGF23) | Age‑related bone turnover decline, estrogen loss |

| Typical labs | High PTH, high phosphate, low calcium, low 1,25‑D | Normal calcium/phosphate, normal PTH |

| Bone turnover | High or low depending on subtype (osteitis fibrosa vs. adynamic) | Usually high turnover |

| Treatment focus | Phosphate binders, vitamin D analogs, calcimimetics | Bisphosphonates, calcium & vitamin D, lifestyle |

| Fracture pattern | Hip & vertebral fractures common, also peripheral | Vertebral & wrist fractures predominate |

By keeping an eye on mineral labs, staying active, and working closely with a nephrologist, you can blunt the impact of kidney disease on your skeleton. Bone loss isn’t an inevitable side‑effect - it’s a modifiable risk that deserves attention.

Julia C

September 29, 2025 AT 16:27It’s frankly unsettling how the medical establishment conveniently glosses over the insidious link between renal failure and skeletal degeneration, as if a silent cabal of pharmaceutical giants is protecting their bottom line. The article dutifully lists hormones and minerals, yet fails to mention the deliberate suppression of alternative therapies that could empower patients. One can’t help but suspect that the very guidelines we trust are filtered through a veil of corporate interests. If only we peeled back the layers of bureaucracy, the truth about kidney‑bone interplay would be crystal clear.

John Blas

October 3, 2025 AT 03:47Wow, another “breakdown” of kidney‑bone science-so groundbreaking, I’m practically weeping with excitement. Yet, the same old tired bullet points, nothing new to stir the soul.

Darin Borisov

October 6, 2025 AT 15:07From a neo‑imperialist perspective, the pathophysiological nexus delineated between chronic renal insufficiency and osteopathic demineralization epitomizes a paradigmatic failure of biomedical hegemony to integrate systemic homeostatic frameworks, thereby perpetuating a colonialist narrative of disease reductionism. The intricate choreography of phosphatemia, calciuria, and parathyroid hormone secretion, when examined through a lens of iatrogenic modulation, reveals a cascade of endocrine dysregulation that is both predictive and prescriptive of skeletal fragility. Moreover, the emergent fibroblast growth factor‑23 axis, a relatively nascent biomarker, functions as a sentinel of phosphate overload, yet its clinical utility is obfuscated by institutional reticence to disseminate nuanced therapeutics beyond the purview of entrenched pharmaceutical monopolies. In juxtaposing the hemodialytic milieu with osteoporotic phenotypes, one discerns a convergence of microarchitectural compromise, wherein trabecular attenuation coalesces with cortical porosity, culminating in a biomechanical milieu predisposed to catastrophic fractures. The stratification of renal osteodystrophy into high‑turnover osteitis fibrosa versus low‑turnover adynamic bone disease further underscores the necessity for a calibrated therapeutic algorithm, one that reconciles calcium‑based phosphate binders with calcimimetic agents while eschewing indiscriminate bisphosphonate deployment. Nonetheless, the prevailing clinical dogma, steeped in reductionist paradigms, tends to marginalize the salutary potential of weight‑bearing exercise regimens, despite robust evidence linking mechanical loading to osteoblastogenesis. Furthermore, the dietary injunctions advocating phosphate restriction remain riddled with cultural myopia, neglecting the sociocultural determinants of nutrition that shape patient adherence. The interdependence of renal clearance capacity, measured via estimated glomerular filtration rate, and bone mineral density metrics such as Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry, thus demands a multidisciplinary confluence of nephrology, endocrinology, and orthopedics, a collaborative model conspicuously absent in most health systems. In addition, the specter of vascular calcification looms large when calcium supplementation is indiscriminately prescribed, a phenomenon that accentuates the paradoxical interplay between mineral homeostasis and cardiovascular morbidity. Consequently, the clinician must navigate a therapeutic tightrope, balancing hyperphosphatemia mitigation against the iatrogenic propagation of calcific vasculopathy. It is incumbent upon policy makers to allocate resources toward longitudinal cohort studies that elucidate the long‑term sequelae of current intervention strategies, thereby transcending the myopic focus on short‑term biochemical normalization. Ultimately, a holistic, patient‑centric paradigm that integrates biochemical monitoring, lifestyle modification, and judicious pharmacotherapy stands as the optimal conduit for attenuating renal‑associated bone loss, a vision that remains aspirational within the current fragmented care continuum. The integration of patient‑reported outcome measures into routine follow‑up can illuminate quality‑of‑life dimensions often eclipsed by laboratory thresholds. Moreover, emerging data on gut microbiome modulation suggest a potential avenue for attenuating phosphate absorption, an area ripe for translational research. Clinicians should also be vigilant for secondary hyperparathyroidism refractory to conventional therapy, as this may herald a transition to tertiary hyperparathyroidism requiring surgical intervention. In sum, the confluence of renal insufficiency and skeletal compromise demands an ecosystemic approach, lest we perpetuate a cycle of morbidity that could be mitigated through interdisciplinary stewardship.

Sean Kemmis

October 10, 2025 AT 02:27It's wrong to ignore the moral obligation of doctors to address bone loss in kidney patients

Nathan Squire

October 13, 2025 AT 13:47Oh, sure, because managing phosphate binders is exactly what everyone signs up for on a Friday night-nothing says fun like counting milligrams of phosphorus. In all seriousness, though, a pragmatic approach starts with a simple food diary to flag hidden phosphates, then coordinate with your nephrologist to choose the appropriate binder-sevelamer if you’re worried about calcium load, or calcium acetate when calcium is low. Adding an active vitamin D analogue can tame secondary hyperparathyroidism, but dose titration is key; too much and you risk hypercalcemia. Finally, a modest regimen of weight‑bearing exercise, even just brisk walking three times a week, goes a long way toward preserving bone density.

satish kumar

October 17, 2025 AT 01:07Indeed, while the presented data are comprehensive, one must question the underlying assumptions, particularly the homogeneity of the patient cohorts, the variability in assay calibration, and the extrapolation of findings to diverse ethnic populations; consequently, the conclusions, though well‑intentioned, may inadvertently oversimplify a complex clinical reality, thereby warranting a more nuanced discussion, perhaps integrating longitudinal outcome measures and stratified risk assessments, which remain conspicuously absent from the current discourse.

Matthew Marshall

October 20, 2025 AT 12:27Honestly, all this hype about kidney‑related bone loss is just another excuse for pharma to profit.

Lexi Benson

October 23, 2025 AT 23:47Great, another checklist of what to avoid-because obviously we all have time to memorize phosphoric acid, pyrophosphate, and the entire chemistry textbook while waiting for dialysis. :)

Vera REA

October 27, 2025 AT 10:07The connection between renal function and skeletal health is indeed fascinating, and it highlights the importance of a holistic view of patient care. Keeping an eye on those labs and staying active can make a real difference.

John Moore

October 30, 2025 AT 21:27Let's remember that each patient’s journey is unique, so collaborating across specialties is essential to tailor the right balance of diet, medication, and exercise. By sharing knowledge and staying open‑minded, we can reduce fracture risk without compromising kidney treatment.

Kimberly Dierkhising

November 3, 2025 AT 08:47When we talk about CKD‑associated osteodystrophy, it’s crucial to differentiate between high‑turnover osteitis fibrosa and low‑turnover adynamic bone disease, as each demands a distinct therapeutic algorithm. Engaging patients in shared decision‑making, while demystifying terms like FGF23 and PTH, fosters adherence and empowers them to navigate their care plan.