When opioids are prescribed for severe pain, they work quickly and effectively. But for many, what starts as a short-term solution becomes a dangerous long-term reality. The problem isn’t just addiction-it’s something quieter, more insidious: tolerance. Your body adapts. The same dose no longer brings the same relief. So you take more. And then more again. That’s how a medical treatment turns into a life-threatening cycle.

How Tolerance Builds-And Why It’s Dangerous

Tolerance doesn’t happen overnight. It starts at the cellular level. Opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors in your brain and spinal cord, blocking pain signals and triggering dopamine release. That’s why they feel good-not just relieving pain, but creating a sense of calm or euphoria. But with repeated use, those receptors become less responsive. They downregulate. They get internalized. Your body tries to balance the constant flood of opioids by reducing its own sensitivity. This isn’t just about needing a higher dose for pain relief. It’s about the body losing its ability to regulate basic functions. The most dangerous part? Tolerance to respiratory depression develops much slower than tolerance to pain relief or euphoria. That means you might be able to take a much higher dose without feeling high anymore-but your breathing still slows dangerously. You can feel fine, but your body is on the edge. A 2021 CDC report showed that 80,411 people in the U.S. died from opioid overdoses that year. Many of those deaths happened because someone took what they used to take before tolerance built up-only to find their body no longer had the safety buffer.Dependence Isn’t the Same as Addiction-But It’s Just as Risky

Dependence means your body physically relies on the drug to function normally. Stop taking it, and you get sick: sweating, nausea, muscle aches, anxiety, insomnia. This isn’t weakness. It’s biology. Your nervous system has rewired itself to expect opioids. When they’re gone, it goes into shock. Dependence can happen even in people who take opioids exactly as prescribed. A 2019 study in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management found that 32% of patients on long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain developed misuse behaviors within a year-not because they were chasing highs, but because their pain got worse and their tolerance kept rising. Addiction is different. It’s compulsive use despite harm. But dependence is what traps people. You don’t need to be addicted to overdose. You just need to be dependent and then miss a dose, get sick, or relapse after a break.Why Relapse Is So Deadly

One of the most misunderstood facts about opioid overdose is this: the biggest risk isn’t new users-it’s people who’ve been clean. When someone stops using opioids-even for a few weeks-their tolerance drops fast. Their body forgets how to handle the drug. But their cravings? They don’t fade. So when they use again, they often take their old high dose. That’s when disaster strikes. A 2017 study in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment found that 65% of opioid overdose deaths occurred in people who had previously been treated for opioid use disorder. One Reddit user wrote: “After 6 months clean, I used my old dose and nearly died-paramedics said I was clinically dead for 4 minutes.” That’s not rare. Harm reduction groups report that 87% of naloxone reversals since 2018 involved people who had been abstinent. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about biology. Your body’s tolerance resets. Your brain still remembers the high. And the gap between those two things kills.

Fentanyl: The Silent Killer in the Drug Supply

The opioid crisis changed when illicit fentanyl flooded the market. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. A dose the size of a few grains of salt can stop your breathing. And it’s mixed into other drugs-heroin, cocaine, counterfeit pills-without users knowing. In 2021, synthetic opioids like fentanyl were involved in 70.3% of all opioid overdose deaths in the U.S., up from just 19.5% in 2015. That’s a 1,200% increase in seizures by the DEA between 2015 and 2022. People aren’t using opioids to get high anymore-they’re using them because they think they’re taking something else. Even experienced users can’t predict how strong a fake pill is. There’s no safe way to test it. No way to know if the powder you bought is 10% fentanyl or 90%. That’s why naloxone-the overdose reversal drug-is now essential for anyone using opioids, even occasionally.Buprenorphine: A Safer Alternative

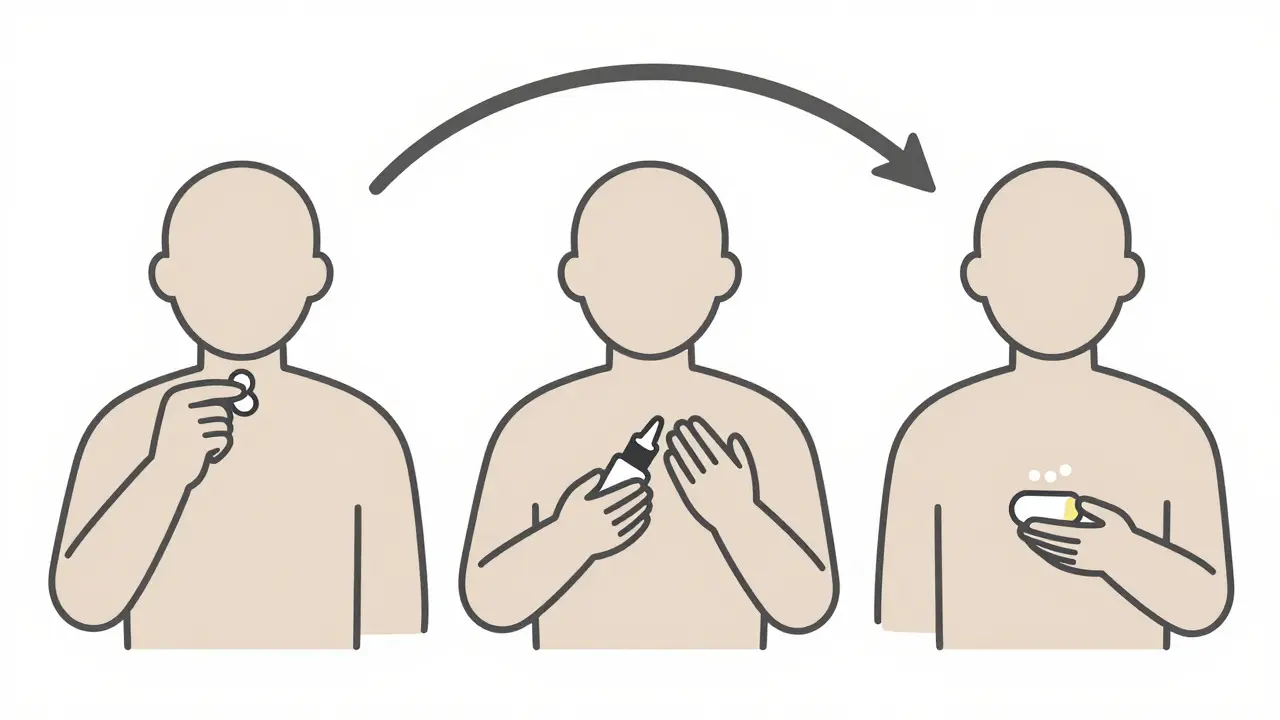

Not all opioids are equally dangerous. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist. That means it activates opioid receptors, but only up to a point. It doesn’t cause the same level of respiratory depression as full agonists like heroin, oxycodone, or fentanyl. Because of this “ceiling effect,” buprenorphine has a much lower risk of fatal overdose. That’s why it’s used in Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT). A 2020 Cochrane Review found that MAT with buprenorphine or methadone reduces overdose risk by 50%. And since the 2023 Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act eliminated the X-waiver requirement, nearly all U.S. doctors can now prescribe it-up from 150,000 to 1.1 million providers. It’s not a cure. But it’s a lifeline. It stabilizes people, reduces cravings, and lets them rebuild their lives without the daily fear of overdose.

What You Can Do-If You or Someone You Know Uses Opioids

If you’re prescribed opioids:- Ask your doctor about non-opioid pain management options.

- Never increase your dose without medical advice.

- Keep naloxone on hand. It’s safe, easy to use, and can save a life.

- Don’t try to go cold turkey alone. Withdrawal is brutal-and relapse is deadly.

- Look into MAT programs. Buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone can help.

- Connect with support groups. You’re not alone.

- Always test your drugs with fentanyl strips-they’re cheap and accurate.

- Never use alone. Have someone nearby who knows how to use naloxone.

- Carry naloxone. Even if you think you’re “used to it,” you’re not immune.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Just About Individuals

Opioid overdose deaths aren’t just personal tragedies-they’re a failure of systems. Prescriptions spiked in the 1990s and 2000s, pushed by aggressive marketing. When crackdowns came, many turned to cheaper, deadlier street drugs. Meanwhile, treatment access lagged behind. The good news? Things are shifting. The CDC reports opioid prescribing rates dropped from 81.3 prescriptions per 100 people in 2012 to 46.7 in 2021. The NIH has invested $1.5 billion since 2023 into non-addictive pain treatments. Naloxone is now available over the counter in many states. And the FDA now requires opioid manufacturers to fund education on tolerance and overdose risk. But the core problem remains: tolerance. It’s built into the biology of these drugs. No matter how good the policy, no matter how many pills are prescribed or restricted, as long as opioids are used, tolerance will follow. And with it, the risk of overdose. The answer isn’t just more law enforcement or more abstinence campaigns. It’s harm reduction. It’s access to medication. It’s understanding that tolerance isn’t a moral failing-it’s a physiological reality. And it’s something we can plan for, prepare for, and prevent.Can you become dependent on opioids even if you take them exactly as prescribed?

Yes. Physical dependence can develop after just a few weeks of regular opioid use-even when taken exactly as directed by a doctor. This is a normal biological response, not a sign of addiction. Dependence means your body has adapted to the drug and will experience withdrawal symptoms if you stop suddenly. That’s why doctors recommend tapering off slowly under medical supervision.

Is naloxone safe to use if I’m not sure someone is overdosing?

Yes. Naloxone only works if opioids are present in the system. If someone isn’t overdosing on opioids, naloxone will have no effect and won’t harm them. It’s safe to administer if you suspect an opioid overdose-especially since signs like slow breathing or unresponsiveness can be hard to recognize. When in doubt, use it. It could save a life.

Why do people overdose after being clean for months?

Tolerance drops quickly after stopping opioid use. After weeks or months without the drug, your body forgets how to handle it. But cravings and old habits don’t disappear. So when someone uses their previous high dose, their body can’t cope. This is why relapse is the leading cause of fatal overdose-even more than initial use. Many overdose deaths happen in people who’ve completed treatment or been sober for a while.

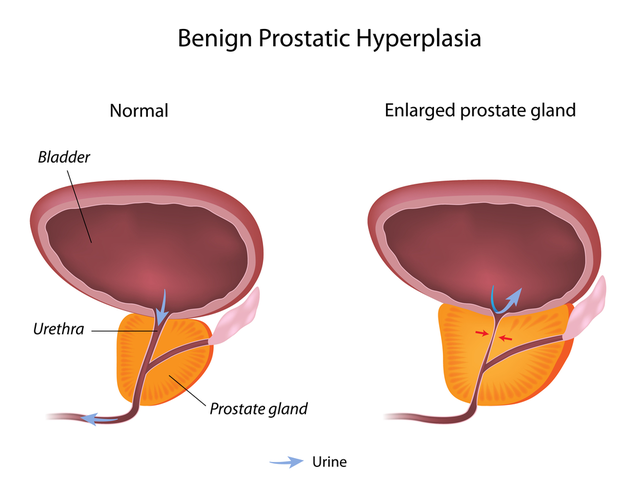

Are prescription opioids safer than street drugs like heroin or fentanyl?

Prescription opioids are regulated and dosed consistently, which makes them safer than street drugs-but they carry the same risks of tolerance, dependence, and overdose. The danger increases when people take higher doses than prescribed, mix them with alcohol or sedatives, or switch to street drugs after their prescription runs out. Fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills are now a major threat, even for people who only ever used prescription pills.

Can buprenorphine help someone who’s already dependent on opioids?

Yes. Buprenorphine is one of the most effective treatments for opioid dependence. It reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms without causing the same level of euphoria or respiratory depression as full agonists like oxycodone or fentanyl. It’s often used in Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) and has been shown to cut overdose risk by half. It’s not a magic fix, but it gives people the stability they need to rebuild their lives.

Is it possible to use opioids long-term without developing tolerance?

No. Tolerance is a universal biological response to repeated opioid exposure. Everyone who uses opioids regularly will develop some level of tolerance over time. The rate varies by person, dose, and duration, but it’s inevitable. That’s why long-term opioid use for chronic pain is no longer recommended as a first-line treatment by most medical guidelines. Non-opioid therapies and careful monitoring are now the standard of care.

Shreyash Gupta

December 26, 2025 AT 06:00Okay but have y’all ever thought that maybe tolerance isn’t the problem… it’s the *expectation*? Like we treat pain like it’s a bug to be deleted, not a signal? 🤔 I mean, if your body adapts, maybe it’s trying to tell you something. Not to take more… but to move differently. Pain isn’t the enemy. The fear of it is.

Dan Alatepe

December 27, 2025 AT 05:15Bro. I seen this in Lagos. Man took oxycodone for a back injury… ended up buying fake blue M30s off a guy who said ‘it’s the same thing’. He woke up in the hospital with his wife screaming and a naloxone vial in his hand. 😭 Tolerance don’t care where you from. It just… takes.

Angela Spagnolo

December 28, 2025 AT 07:28I… I didn’t know naloxone was available over the counter now. I’ve been terrified to carry it, like if I did, I’d be admitting someone I love might die. But reading this… I bought two. I keep one in my purse, one in my car. I’m not brave. I’m just tired of losing people. 💔

Sarah Holmes

December 28, 2025 AT 11:18It is profoundly disturbing that our society has normalized the idea that biological adaptation to a psychoactive substance is somehow a ‘failure of will.’ This is not a moral failing-it is a biochemical betrayal engineered by pharmaceutical marketing and institutional neglect. We have criminalized physiology. We have pathologized survival. And we wonder why people die.

Jay Ara

December 29, 2025 AT 19:00my cousin did 2 years clean then took a pill he thought was oxycodone… turned out it was fentanyl. he didn’t even know he was using. naloxone saved him. now he’s on buprenorphine and working at a rehab center. it’s not about being strong. it’s about being smart. you don’t have to do it alone

Michael Bond

December 31, 2025 AT 04:44Buprenorphine works. Just saying.

Lori Anne Franklin

January 1, 2026 AT 03:39i used to think if you were careful you could use them forever… turns out biology doesn’t care how careful you are. i’m 3 years clean now, and i still get nervous when i see a blue pill. but i carry naloxone. i tell everyone i know to do the same. it’s not about fear. it’s about love.

Bryan Woods

January 1, 2026 AT 10:10The CDC data on tolerance lagging behind euphoria is perhaps the most chilling statistic in modern public health. It means people can feel fine while their brainstem is shutting down. That’s not addiction. That’s a silent countdown.

Ryan Cheng

January 2, 2026 AT 20:32If you’re reading this and you’re scared to ask for help-know this: you’re not weak. You’re human. Buprenorphine isn’t replacing one drug with another. It’s giving your nervous system a chance to heal. I’ve seen people come back from the edge. It’s not magic. But it’s real. And you deserve it.