When you pick up a generic prescription at the pharmacy, you might assume the price you pay is simple: cheaper than the brand name, end of story. But behind that $4.50 copay or $12 out-of-pocket cost is a tangled web of federal laws, state regulations, and corporate contracts that decide exactly how much the pharmacy gets paid-and who absorbs the difference. These aren’t just accounting details. They affect whether a pharmacist can tell you a drug is cheaper without insurance, whether your local independent pharmacy stays open, and even whether you get the medicine you need at all.

How Generic Drugs Are Paid For: The Two Main Models

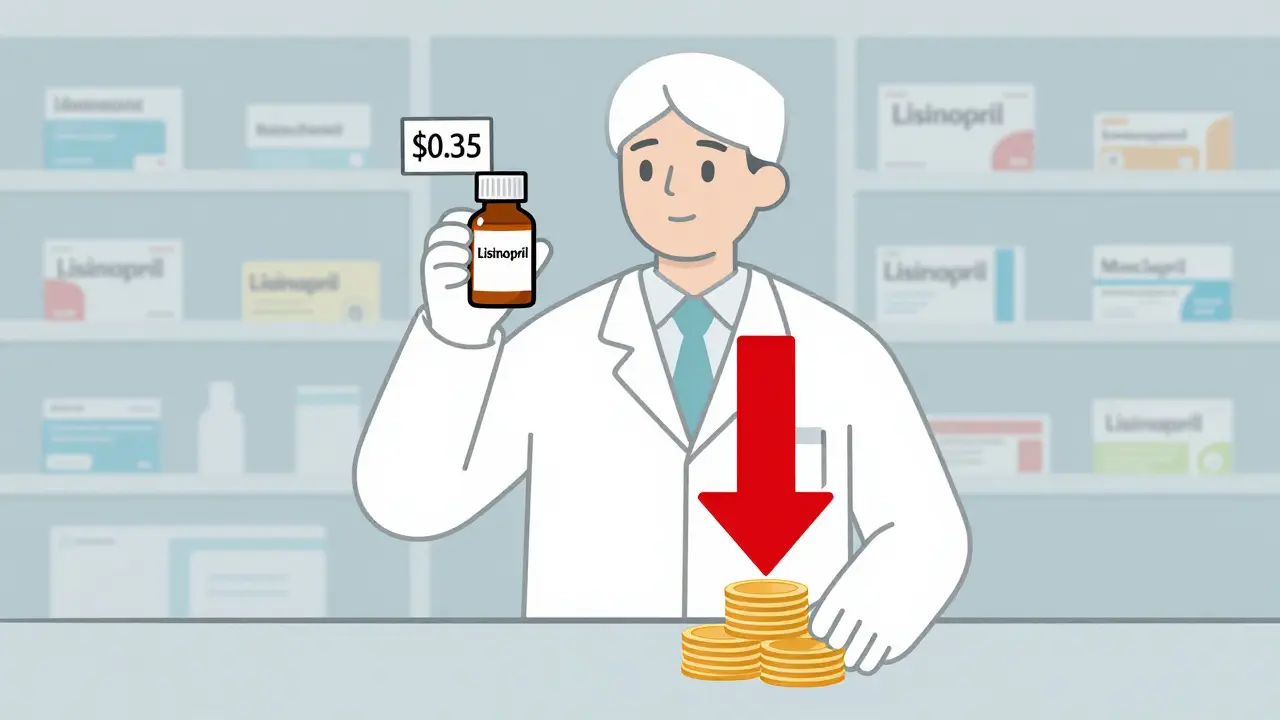

Pharmacies don’t get paid the same way for every drug. For generics, reimbursement mostly runs through two systems: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). AWP was once the standard, using a list price published by drug manufacturers that often had little to do with what pharmacies actually paid. Today, most plans have moved away from AWP for generics because it inflated costs. MAC is now the norm.MAC programs set a fixed payment limit per unit-say, $0.35 for a 30-pill bottle of lisinopril. If the pharmacy buys it for $0.30, they keep the $0.05. If they pay $0.40? They eat the loss. This model was designed to keep costs down, but it’s created a squeeze. In 2023, the average profit margin on generic drugs for independent pharmacies was just 1.4%. Five years earlier, it was 3.2%. Many small pharmacies are operating on pennies per script.

Medicare Part D: The Biggest Player with Complex Rules

Medicare Part D covers over 50 million seniors and disabled Americans. It’s the largest driver of generic drug reimbursement in the U.S. But it’s not one system-it’s a patchwork. Part D plans must cover FDA-approved drugs used for medically accepted purposes, but each plan decides which generics go on which tier. Lower tiers mean lower copays. Higher tiers mean higher costs-or no coverage at all.As of 2022, nearly 3 out of 10 Part D plans required prior authorization for at least one generic drug. That means your doctor has to call in paperwork before the pharmacy can fill it. Meanwhile, the plan may pay the pharmacy a fixed dispensing fee-$4 to $8 per script-on top of the MAC reimbursement. Some plans even offer bonuses if pharmacists hit targets for dispensing generics instead of brand-name drugs.

But here’s the catch: Part D has a coverage gap, known as the “donut hole.” Even though generics are cheaper, if your total drug spending hits a certain threshold, you pay more out of pocket until you reach catastrophic coverage. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped out-of-pocket costs at $2,000 starting in 2025, which should help-but it doesn’t fix how the system pays pharmacies.

What PBMs Do-and How They Make Money

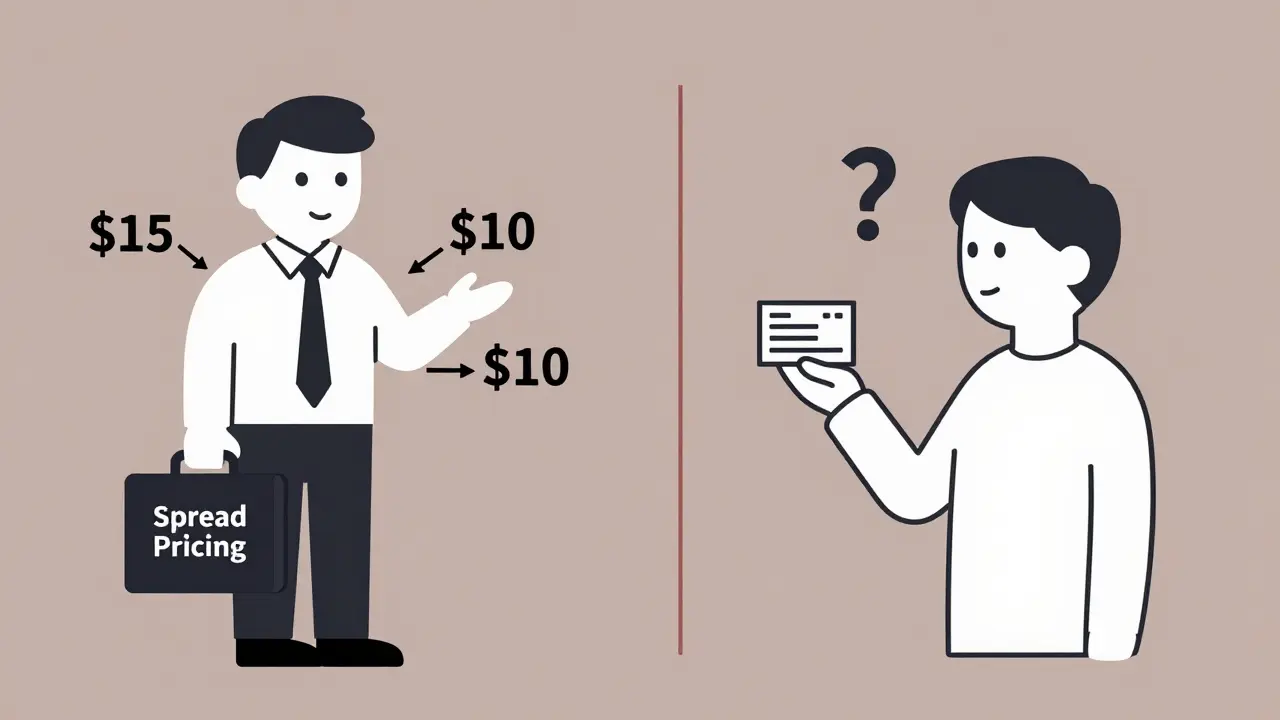

Behind most insurance plans are Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX control over 80% of prescription claims in the U.S. They negotiate with drug makers, set formularies, and determine how much pharmacies get paid. But their business model has been called out for creating perverse incentives.PBMs earn money in three main ways: rebate shares from drug makers, spread pricing, and owning their own pharmacies. Spread pricing is the trickiest. It’s the difference between what the insurer pays the PBM and what the PBM pays the pharmacy. For example: the insurer pays the PBM $15 for a generic drug. The PBM pays the pharmacy $10. The $5 difference? That’s profit for the PBM. And until 2018, many PBMs had “gag clauses” that legally prevented pharmacists from telling customers they could pay cash for less than their copay.

Independent pharmacies often have no choice but to accept these terms. If they don’t join the PBM’s network, they lose most of their business. But when MAC prices drop below what they can buy the drug for, they lose money on every script. That’s why so many small pharmacies are closing or being bought out by big chains.

State Laws Are Changing the Game

While federal rules set the stage, states are stepping in. As of early 2023, 44 states passed laws regulating how PBMs reimburse pharmacies for generics. Some require PBMs to pay at least the pharmacy’s actual acquisition cost. Others ban spread pricing entirely. A few even require PBMs to disclose their pricing formulas.States also run Medicaid programs with Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). These lists determine which generics are covered and which require prior authorization. The state’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee decides which drugs are preferred-and why. A drug might be preferred because it’s cheaper, or because it’s been on the market longer, or because the manufacturer gave a bigger rebate. It’s not always about clinical need.

The $2 Drug List: A New Experiment

In 2025, CMS launched a voluntary model called the “$2 Drug List.” It’s simple: select about 100 to 150 low-cost, high-use generic drugs and cap patient copays at $2. The goal? Improve adherence, reduce confusion, and cut administrative waste. Drugs are chosen based on clinical importance, frequency of use among Medicare patients, and whether they’re already on preferred formulary tiers.This model mirrors what Walmart and Costco already do: fixed-price generics you can buy without insurance. But it’s the first time Medicare is trying to standardize this across all Part D plans. If it works, it could become the new baseline. If not, it might be scrapped. Either way, it’s a signal: the old reimbursement system is under pressure to change.

Why This Matters for Patients and Pharmacists

It’s easy to think reimbursement models are just a back-office issue. But they directly affect your health. If a pharmacy can’t afford to stock a generic because the reimbursement is too low, they might not carry it. If they’re losing money on every script, they might not have the staff to answer your questions or check for interactions.Patients with low incomes benefit from Extra Help programs, paying no more than $4.50 for generics in 2024. But those without subsidies face unpredictable costs. One person might pay $5 for a generic because their plan has it on tier one. Another might pay $25 because their plan doesn’t cover it-or puts it on a high tier. That’s not based on the drug’s value. It’s based on contract negotiations between PBMs and insurers.

And then there’s the “authorized generic” loophole. Sometimes, the brand-name company releases its own generic version-same ingredients, same packaging, just a different label. It undercuts competitors before they even get started. This practice, allowed under current patent laws, reduces competition and keeps prices higher than they should be.

What’s Next?

The pressure is building. Generic drug prices are falling an estimated 5-7% per year through 2027. PBMs are under scrutiny from the FTC and Congress. Independent pharmacies are organizing to demand fair reimbursement. States are pushing for more transparency. And CMS is testing whether a simpler, fixed-price model works better than a complex, opaque one.The future of generic drug reimbursement won’t be decided in a single law. It’ll come from a mix of federal experiments, state regulations, court rulings, and consumer pressure. But one thing is clear: the current system is broken for pharmacies and confusing for patients. Real change will come when the focus shifts from cutting costs to ensuring access-and when pharmacists are finally paid fairly for the service they provide.

Why do pharmacies sometimes lose money on generic drugs?

Pharmacies lose money on generics when the reimbursement rate-set by Medicare, Medicaid, or a PBM-is lower than what the pharmacy actually paid to buy the drug. This happens under Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) programs, where the payer caps the reimbursement at a fixed amount. If the pharmacy’s cost is higher than that cap, they absorb the difference. In 2023, average generic drug margins fell to just 1.4%, down from 3.2% in 2018, pushing many small pharmacies to the edge.

What’s the difference between MAC and AWP reimbursement?

AWP (Average Wholesale Price) was an outdated list price set by drug manufacturers that often didn’t reflect real costs. It was used to calculate reimbursement by subtracting a percentage from AWP. MAC (Maximum Allowable Cost) is a real-world price cap based on what pharmacies actually pay for generics. MAC is now the standard for generics because it’s more accurate and helps control costs. AWP is mostly used today for brand-name drugs still under patent.

Can pharmacists tell me if a drug is cheaper without insurance?

Yes, since 2018, federal law banned “gag clauses” that prevented pharmacists from informing patients about lower cash prices. If a generic drug costs less out-of-pocket than your insurance copay, your pharmacist can now tell you. Many pharmacies even post cash prices on their websites or apps. Always ask-you might save money.

How do PBMs affect generic drug prices?

PBMs control most prescription claims in the U.S. and set reimbursement rates for pharmacies. They earn money through rebates from drug makers, spread pricing (the gap between what insurers pay and what pharmacies get), and owning their own pharmacies. This creates a conflict: PBMs benefit when brand-name drugs are used because rebates are higher. They also pressure pharmacies with low MAC rates, which can limit access to generics. Their lack of transparency makes it hard for patients and pharmacists to understand true costs.

What is the Medicare $2 Drug List?

The Medicare $2 Drug List is a new voluntary model launched in 2025. It aims to simplify Part D by capping copays at $2 for about 100-150 low-cost, high-use generic drugs. Drugs are selected based on clinical importance, frequency of use among Medicare patients, and whether they’re already on preferred formulary tiers. The goal is to improve adherence and reduce confusion. If successful, it could become a national standard for generic drug pricing.

Why are some generic drugs not covered by insurance?

Insurance plans use formularies to control costs. A generic drug might not be covered-or might require prior authorization-if it’s not on the preferred list. This can happen because the manufacturer didn’t offer a good rebate, the drug is newer, or the plan’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee chose a different version. Even if a drug is FDA-approved, it doesn’t guarantee coverage. Always check your plan’s formulary before filling a prescription.

Alex Flores Gomez

January 28, 2026 AT 17:24So let me get this straight - we’re paying pharmacists less than the cost of the pills they hand out? And we wonder why small pharmacies are vanishing like dial-up modems? This isn’t healthcare, it’s a casino where the house always wins. PBMs are the real drug dealers here, and we’re all just chumps playing along. #PharmacyCrisis

Frank Declemij

January 29, 2026 AT 13:45MAC reimbursement rates must reflect actual acquisition cost. The current model incentivizes underpayment and erodes pharmacy viability. Federal oversight is insufficient; state-level reforms like those in California and New York demonstrate that transparency and cost-based reimbursement are feasible and necessary.

Pawan Kumar

January 29, 2026 AT 22:56Did you know the FDA and CMS are in cahoots with Big Pharma to suppress generic competition? The $2 drug list is a distraction - a psyop to make you think change is coming. Meanwhile, the same corporations that own PBMs also own the patents on the 'authorized generics' that kill real competition. Wake up. This is controlled demolition of independent access.

DHARMAN CHELLANI

January 31, 2026 AT 04:29Why are we even talking about this? Everyone knows PBMs are crooks. Pharmacies get robbed. Patients get confused. End of story. Stop overcomplicating it. Just pay them what they paid for the pills. Done.

Robin Keith

February 2, 2026 AT 02:01It’s not just about money - it’s about dignity. The pharmacy is supposed to be a sanctuary of care, a quiet corner where someone listens to your worries, checks your interactions, remembers your allergies - but now? They’re just automated kiosks running on fumes, hemorrhaging pennies per script, terrified to look you in the eye because they can’t afford to give you the truth. We’ve turned healing into a spreadsheet. And we wonder why people don’t trust the system anymore? It’s because the system has no soul. We’re not just losing pharmacies - we’re losing the last vestige of human care in medicine. 😔

Sheryl Dhlamini

February 2, 2026 AT 08:07My grandma used to get her lisinopril for $4 at the corner drugstore. Now she has to wait 3 days for prior auth and still gets charged $12 because the PBM says it’s 'not preferred.' I called the pharmacy yesterday - the pharmacist cried. Not dramatic. Just… tired. We’re letting people suffer because someone’s quarterly report needs a better number.

Doug Gray

February 3, 2026 AT 20:42So the MAC model creates negative margins → PBM spread pricing exacerbates → independent pharmacies are squeezed → consolidation follows → market power concentrates → regulatory capture ensues. Classic vertical integration arbitrage with healthcare as the asset. The $2 list is a band-aid on a hemorrhage. We need structural reform, not symbolic gestures. 🤷♂️

LOUIS YOUANES

February 4, 2026 AT 00:29They don’t pay pharmacists enough to care. So why should they care if you take your meds? They’re just scanning barcodes and hoping you don’t ask too many questions. And the worst part? They know they’re being ripped off. But they’re too broke to fight back. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy logo.