TZD Safety Checker

Patient Risk Assessment

This tool evaluates your heart failure risk when considering thiazolidinediones (TZDs). Based on current guidelines from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association.

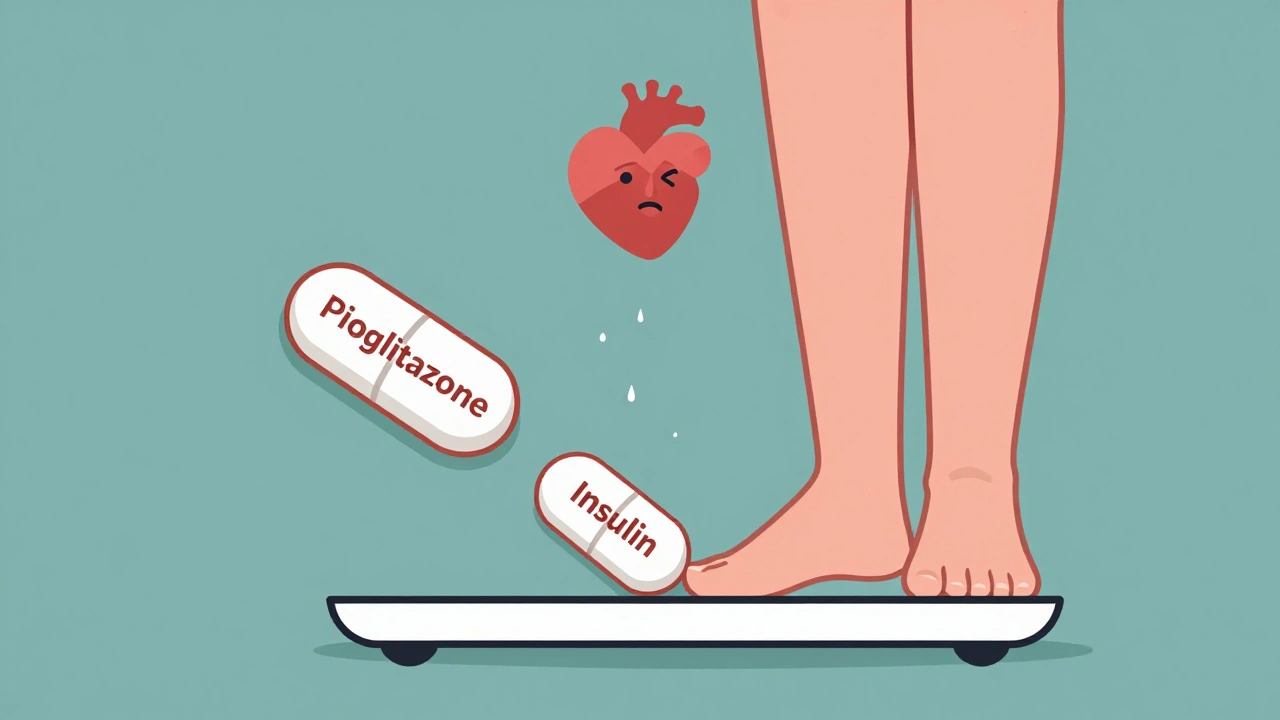

When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing low glucose episodes is a win. Thiazolidinediones - like pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia) - used to be go-to drugs for exactly that. They make your body respond better to insulin, helping control blood sugar without the risk of hypoglycemia that comes with insulin or sulfonylureas. But behind their effectiveness lies a quiet, dangerous side effect: fluid retention. And for people with heart problems, that can be life-threatening.

How Thiazolidinediones Work - and Why They Cause Swelling

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) activate a protein called PPAR-γ, found in fat, blood vessel, and kidney cells. This boosts insulin sensitivity, which is great for blood sugar. But PPAR-γ is also active in the kidneys, where it triggers sodium and water reabsorption. That’s the problem. Your body holds onto more fluid than it should. In healthy volunteers, TZDs increase blood volume by 6-7%. That extra fluid doesn’t just sit quietly - it pools in the ankles, legs, and sometimes lungs.

It’s not just one mechanism. Some studies show TZDs turn on sodium channels in the kidney’s collecting ducts via SGK-1, while others suggest they block chloride transport or activate other sodium pathways. The exact process isn’t fully settled, but the result is clear: your kidneys hold onto salt and water like a sponge. That’s why patients on TZDs often see their hematocrit drop - not because they’re losing red blood cells, but because their plasma volume expands.

How Common Is Fluid Retention?

Fluid retention isn’t rare. About 5-7% of people taking TZDs alone develop noticeable swelling in their legs or feet. That number jumps to 15% when TZDs are combined with insulin. In one study of 111 diabetic patients with existing heart failure, nearly 1 in 6 (17.1%) gained at least 10 pounds and developed swelling - and 2 of them ended up with fluid in their lungs.

Women are more likely to experience this than men. So are people already on insulin. Age and obesity don’t seem to matter as much - but having heart failure does. And here’s the scary part: nearly half of all people currently taking TZDs already show signs of heart failure before they even start the drug. A 2018 analysis of over 424,000 U.S. diabetic patients found that 40.3% of TZD users had either a heart failure diagnosis, reduced heart pumping ability (ejection fraction under 40%), or were already taking loop diuretics. That’s not a coincidence. That’s a red flag.

When Fluid Retention Turns Dangerous

Swollen ankles are one thing. Pulmonary edema - fluid in the lungs - is another. That’s when breathing becomes labored, even at rest. It’s not just uncomfortable. It’s an emergency. In patients with pre-existing heart disease, TZD-induced fluid retention can push a stable condition into decompensated heart failure. The American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association agree: TZDs can be used in people with mild, stable heart failure (NYHA Class I-II), but only with close monitoring. They’re absolutely off-limits for those with severe heart failure (NYHA Class III-IV).

What makes this worse is that TZD-related fluid retention doesn’t always respond well to diuretics. Loop diuretics like furosemide - the go-to for heart failure - often fail to clear the excess fluid. The only sure fix? Stopping the drug. Within days of discontinuation, swelling typically goes down, and heart function improves.

Who Should Never Take Thiazolidinediones?

Based on current guidelines, TZDs are contraindicated in:

- Patients with active or recent heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV)

- People with a history of pulmonary edema

- Those already on insulin who show early signs of swelling

- Patients with severe kidney disease

Even if someone doesn’t have a formal heart failure diagnosis, if they’re on diuretics, have a low ejection fraction, or have had heart failure in the past, TZDs should be avoided. The 2020 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines are blunt: don’t use TZDs in patients with heart failure or at high risk for it. And with 40% of current users already showing signs of heart problems, that’s a lot of people.

Why Are People Still Taking Them?

Despite the risks, TZDs haven’t disappeared. About 8.3% of U.S. diabetic patients on glucose-lowering meds still take them. Why? Because they work - really well. They lower HbA1c by 1-1.5%, without causing low blood sugar. They may also have benefits for artery health, reducing inflammation and plaque buildup. For some patients - especially those with severe insulin resistance and no heart disease - the benefits still outweigh the risks.

But here’s the catch: many prescribers aren’t screening properly. The 2018 study found that nearly half of TZD users had undiagnosed or unacknowledged heart failure. That’s not just a gap in knowledge - it’s a safety failure. Patients aren’t being asked about swelling, weight gain, or shortness of breath before starting the drug. And once it’s started, weight isn’t tracked weekly, as recommended.

What Should You Do If You’re on a TZD?

If you’re taking pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, here’s what you need to do:

- Check your weight every week. A gain of 2-3 pounds in a week is a warning sign.

- Watch for swelling in your ankles, legs, or abdomen.

- Notice if you’re getting winded faster - climbing stairs, walking to the mailbox, even lying flat.

- Ask your doctor for an echocardiogram if you haven’t had one in the last year - especially if you’re over 65 or have high blood pressure.

- If you develop any of these signs, don’t wait. Call your doctor. Don’t try to tough it out.

Don’t stop the drug on your own. But don’t ignore the signs either. The risk isn’t theoretical. It’s real, measurable, and preventable.

The Bottom Line

Thiazolidinediones are powerful tools for diabetes - but they’re not safe for everyone. Their ability to cause fluid retention is well-documented, predictable, and dangerous in people with heart conditions. The FDA requires a black box warning for this exact reason. Yet, too many patients are still being prescribed these drugs without proper screening.

The data doesn’t lie: nearly half of current users have signs of heart failure. That’s not an accident. It’s a systemic failure in patient selection and monitoring. If you’re considering TZDs, ask your doctor: “Have I been checked for heart failure?” If you’re already on one, ask: “Am I being monitored for fluid retention?”

There are safer alternatives now - SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists - that lower blood sugar, protect the heart, and actually reduce fluid retention. TZDs have a place, but only for a small group of patients: those with no heart disease, no swelling, no diuretics, and no history of heart problems - and even then, only with weekly weight checks and a plan to stop immediately if anything changes.

For most people with diabetes and heart risks, the old days of TZDs as a first-line option are over. The science is clear. The risks are real. And the safer choices are here.

Can thiazolidinediones cause heart failure in people without it?

Yes, in susceptible individuals - especially those with kidney issues, older adults, or those on insulin - TZDs can trigger new-onset heart failure by causing fluid overload. The drugs don’t damage the heart muscle directly, but the extra fluid increases pressure on the heart, which can overwhelm a weakened system. Studies show that even patients without prior heart disease can develop symptoms like shortness of breath and swelling after starting TZDs.

Is pioglitazone safer than rosiglitazone for the heart?

In terms of fluid retention and heart failure risk, both drugs are equally risky. They work the same way through PPAR-γ activation. Rosiglitazone had additional concerns about heart attacks, leading to restrictions in 2010, but those were later relaxed after follow-up studies. However, neither drug has a safety advantage when it comes to swelling or heart failure. Both carry the same FDA black box warning.

Why don’t diuretics fix the swelling caused by TZDs?

TZDs cause fluid retention through a different mechanism than typical heart failure. While loop diuretics target the loop of Henle, TZDs affect sodium reabsorption in the collecting duct and proximal tubule - areas that respond poorly to standard diuretics. That’s why many patients don’t improve even with high doses of furosemide. The only reliable fix is stopping the TZD.

Are there any alternatives to thiazolidinediones for insulin resistance?

Yes. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (like semaglutide and liraglutide) are now preferred. They improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood sugar, promote weight loss, and - importantly - reduce heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular death. Unlike TZDs, they actually remove fluid from the body, making them safer and more beneficial for people with diabetes and heart risks.

How often should weight be checked when starting a TZD?

Weekly. Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and American Heart Association recommend checking weight every week during the first few months of starting a TZD. A gain of more than 2-3 pounds in a week is a red flag for fluid retention. If that happens, the drug should be stopped or the dose reduced, and the patient evaluated for heart failure.

Brian Perry

December 2, 2025 AT 18:10so i was on actos for like 6 months and my ankles looked like i’d been stuffed with balloons?? no joke i had to buy new shoes every 3 weeks. my dr just said "oh that’s normal" like i was complaining about the weather. then i started gaining 5 lbs a week and couldnt breathe lying down. guess what? i stopped it. and boom. went back to normal in 10 days. why do doctors still prescribe this like its a vitamin??

Josh Bilskemper

December 4, 2025 AT 16:14TZDs activate PPARγ which upregulates ENaC and SGK1 in the collecting duct leading to sodium retention. The fluid shift isn't edema from capillary leak its iatrogenic hypervolemia. Diuretics fail because they target the loop not the collecting duct. End of story. Stop prescribing these like they're candy.

Storz Vonderheide

December 4, 2025 AT 22:30Hey everyone - I just want to say this post is incredibly well-researched and important. I'm a nurse in rural Ontario and I've seen too many patients on TZDs who didn't know the risks. We need better screening tools and more education for both docs and patients. Weekly weight checks? Yes. But also asking simple questions like "have you been feeling puffier lately?" or "do your socks leave marks?" can save lives. Let's not make this complicated. Just be present. Be curious. Be kind.

dan koz

December 5, 2025 AT 17:39bro i got prescribed actos after my hba1c hit 8.9 and i was like cool i dont wanna take insulin. 2 months later i couldnt tie my shoes. my wife made me go to the er. they said i had stage 2 heart failure from fluid. i was 38. no preexisting conditions. now im on metformin and semaglutide. the weight dropped off like magic. also my libido came back. who knew diabetes meds could be sexy?

Kevin Estrada

December 7, 2025 AT 06:29you think this is bad wait till you find out the pharma companies knew about this in the 90s but buried the data because TZDs made billions. they even paid doctors to downplay the risks. now theyre pushing SGLT2 inhibitors like they invented them. same companies. same playbook. wake up people. the system is rigged and your meds are the profit margin

Katey Korzenietz

December 7, 2025 AT 17:31My doctor said "it’s just water weight" like I’m a balloon. I cried in the parking lot. I’m 52, female, no heart history. Now I’m on dapagliflozin. I lost 18 lbs. I can walk to the mailbox without gasping. Don’t let them gaslight you. This isn’t normal. It’s poison.

Ethan McIvor

December 7, 2025 AT 23:53it makes me sad how we treat diabetes like a math problem: take this pill, get this number down. but the body isn't a spreadsheet. it's a living, breathing, fragile thing. TZDs are like forcing a garden to grow by pouring salt on the soil - it looks green at first, but the roots are dying. we need to see patients as whole people, not HbA1c numbers. 💔

Michael Bene

December 9, 2025 AT 11:19so let me get this straight - we’ve got a drug that makes your kidneys sponge up fluid like a drunk at a buffet, and we still let people take it? and not just a few - 8% of diabetics? that’s like handing out flamethrowers at a fireworks convention. and the worst part? the docs who prescribe it don’t even check for swelling. they just say "oh you’re gaining weight? just cut back on carbs." bro. your kidneys are holding onto water like it’s the last beer at a party. this isn’t laziness. this is negligence dressed in a white coat.

Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 10, 2025 AT 00:17you think this is about medical negligence? nah. this is about the FDA being bought off. remember Avandia? they pulled it, then put it back because the study was "flawed" - guess who funded the study? GlaxoSmithKline. And now they’re pushing SGLT2 inhibitors like they’re miracle cures - but guess what? same parent company. They just rebranded the poison. They don’t care if you drown in fluid - they care if your insurance pays for it. This isn’t medicine. It’s corporate theater with stethoscopes.

Pamela Mae Ibabao

December 10, 2025 AT 19:56lol i love how people act like this is some new revelation. i’ve been telling my patients for years: if you’re on a TZD and your socks are leaving indentations, STOP. no waiting. no "let’s monitor." just stop. and yes, the weight loss after stopping is dramatic. like, "why am i suddenly able to see my toes" dramatic. also - women get hit harder. always ask about swelling. always. it’s not optional.

Adrianna Alfano

December 12, 2025 AT 00:30my mom died from this. she was 69, on pioglitazone for 18 months. they told her it was "just fluid" and she didn’t want to be a burden. she didn’t say anything until she couldn’t breathe in bed. they found 3 liters of fluid in her lungs. she never had heart failure before. the doctor said "we didn’t know." WE DIDN’T KNOW? she was on a drug with a BLACK BOX WARNING. and you didn’t ask if she was swollen? if she was tired? if she’d gained weight? that’s not ignorance. that’s murder by omission.

May .

December 13, 2025 AT 09:42just stopped my actos last week. lost 12 lbs in 10 days. my feet fit in my shoes again. also my blood pressure dropped. no diuretics. just quit the drug. why is this even a debate?