When a child gets pneumonia or a woman develops a urinary tract infection, the expectation is simple: a few days of antibiotics, and they’ll feel better. But in 2025, that’s no longer guaranteed. Across the globe, antibiotics are running out - not because we’ve cured all infections, but because the system that makes them is breaking down. The result? People are dying from infections that should be easy to treat.

Why Antibiotics Are Disappearing

Antibiotics aren’t like other medicines. They’re cheap, mass-produced, and often generic. That’s why manufacturers stopped investing in them. In 2024, the global antibiotic market was worth $38.7 billion, but it grew by just 1.2% over five years - far below the 5.7% average for all pharmaceuticals. Meanwhile, regulatory costs for making sterile injectables jumped 34% since 2015. For companies, it’s cheaper to make expensive cancer drugs or diabetes pills than to produce penicillin or amoxicillin. The problem got worse after Brexit. In the UK, antibiotic shortages tripled between 2020 and 2023, from 648 to 1,634 cases. In the U.S., the FDA listed 147 active antibiotic shortages by December 2024 - the highest in a decade. The European Economic Area reported 28 countries facing shortages, with 14 calling them “critical.” Some antibiotics have been in short supply for years. Penicillin G benzathine, used to treat syphilis and prevent rheumatic fever, has been unavailable since 2015. Amoxicillin, one of the most common antibiotics for children, saw use drop by 55% in 22 countries after its 2023 shortage. And when these drugs vanish, there’s often no good replacement.What Happens When Antibiotics Run Out

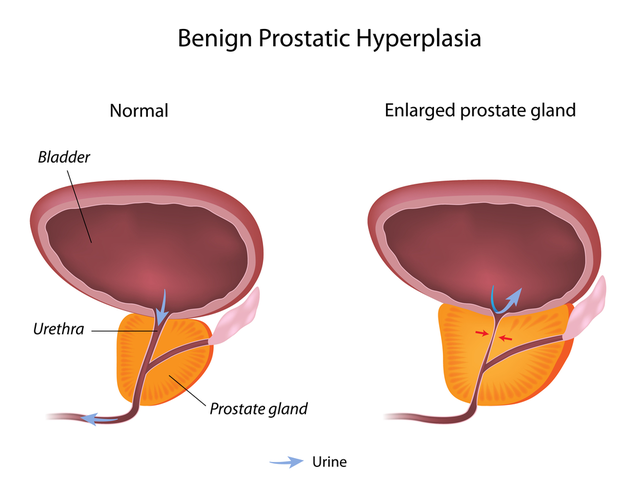

Doctors don’t just delay treatment - they’re forced to choose between two bad options: use a weaker antibiotic that won’t work, or use a stronger one that could cause more harm. When third-generation cephalosporins - first-line drugs for E. coli and K. pneumoniae - disappear, clinicians turn to carbapenems. These are powerful, last-resort antibiotics. But using them too often speeds up resistance. Globally, over 40% of E. coli and 55% of K. pneumoniae are already resistant to these drugs. Every time a doctor reaches for a carbapenem because amoxicillin isn’t available, they’re helping create a superbug. In low-resource settings, the impact is even worse. In rural Kenya, nurses report sending patients home without treatment because penicillin isn’t in stock. In Mumbai, a mother’s child waited 72 hours for azithromycin - the delay turned a simple pneumonia case into a trip to intensive care. The WHO calls this a “syndemic”: where resistance and under-treatment feed each other. In the U.S., 78% of hospital pharmacists said they had to change treatment plans in the past year because of shortages. Sixty-two percent saw more patients get sicker or develop complications. One California infectious disease specialist told the APHA forum she had to use colistin - a toxic, last-resort drug - for a routine UTI. That’s not medicine. That’s triage.

Who’s Most Affected - And Why

Antibiotic shortages don’t hit everyone equally. High-income countries can sometimes import drugs or shift to alternatives. But low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face a double crisis: 70% of antibiotics are already inaccessible there. Even when drugs exist, they’re often too expensive or too far away. The WHO’s Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report 2025 shows resistance is worst in South-East Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean - where one in three infections can’t be treated with standard antibiotics. In Africa, one in five infections are resistant. These regions also have the weakest health systems, the fewest diagnostics, and the least access to alternatives. Meanwhile, in places like the U.S. and Europe, hospitals are overwhelmed by paperwork. Pharmacists spend 22% more time managing shortages. Doctors are forced to guess which drug might work. Nurses track inventory like they’re managing a war zone. The system isn’t broken - it’s being stretched past its limit.What’s Being Done - And Why It’s Not Enough

There are efforts to fix this. The WHO launched a five-point plan in October 2025, including a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative by 2027. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing facilities in January 2025, expected to ease 15% of shortages by late 2025. The European Commission is pushing new rules to guarantee production of critical antibiotics. Hospitals are also trying. Johns Hopkins reduced unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 37% during shortages by using rapid diagnostic tests. California created a regional sharing network that cut critical shortage impacts by 43%. But these are patches - not solutions. The real problem? No one pays enough to make antibiotics profitable. The generic antibiotic market has seen prices drop 27% since 2015. Manufacturers don’t invest in quality because they can’t make money. Regulatory agencies don’t enforce standards tightly enough because they’re underfunded. And governments don’t step in because antibiotics aren’t seen as “valuable” like cancer drugs.

What Needs to Change

Fixing antibiotic shortages isn’t about finding more drugs - it’s about fixing the market. Here’s what works:- Guaranteed minimum purchase agreements - Governments commit to buying a set amount of key antibiotics every year, no matter the price. This gives manufacturers certainty.

- Public manufacturing hubs - Countries like India and China dominate production. A global network of publicly funded, high-standard antibiotic plants could prevent supply chain collapse.

- Antibiotic stewardship programs - Only 37% of U.S. hospitals meet WHO standards for these programs. Better use means less waste and slower resistance.

- Fast-track diagnostics - If doctors know exactly which bacteria they’re fighting, they can avoid broad-spectrum drugs. That preserves the few effective ones we have.

The Human Cost of Waiting

Behind every statistic is a person. A baby in Nairobi who didn’t get penicillin. A grandmother in Detroit who got sepsis because her UTI wasn’t treated on time. A teenager in London who missed school for weeks because amoxicillin was rationed. Antibiotic shortages aren’t just a supply chain issue. They’re a moral one. We’ve spent decades developing new drugs, but we’ve ignored the ones we already have. We treat antibiotics like commodities - not lifesavers. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts that without action, antibiotic shortages will increase by 40% by 2030. That could mean 1.2 million more deaths each year from infections we know how to cure. We’re not running out of science. We’re running out of will.Why are antibiotics in short supply when we need them so badly?

Antibiotics are cheap to make and sold at low prices, so pharmaceutical companies make little profit. Manufacturing costs have risen 34% since 2015 due to stricter regulations, but prices haven’t kept up. Companies focus on more profitable drugs like cancer treatments. This has led to factory closures and reduced production, especially for generic antibiotics that make up 85% of global use.

What happens when doctors can’t get the right antibiotic?

Doctors are forced to use broader-spectrum antibiotics - like carbapenems - even for simple infections. These drugs are more powerful but also increase antibiotic resistance. In some cases, they have to use toxic last-resort drugs like colistin. Patients face longer hospital stays, higher risk of complications, and sometimes death because treatment is delayed or ineffective.

Are there alternatives to the antibiotics that are running out?

For many common infections, there are no equally effective alternatives. For example, when amoxicillin is unavailable, there’s no other oral antibiotic as safe or effective for children. For resistant infections, alternatives are often older, more toxic, or harder to administer. In low-income countries, alternatives may not exist at all. This makes antibiotic shortages uniquely dangerous compared to shortages of other drugs.

How are hospitals coping with antibiotic shortages?

Hospitals are using antimicrobial stewardship programs to track usage, prioritize essential drugs, and reduce unnecessary prescriptions. Some have created regional sharing networks to distribute limited supplies. Pharmacists are spending 22% more time managing inventory. But these are temporary fixes. Many hospitals lack the resources to implement these systems properly, especially in rural or underfunded areas.

Can importing antibiotics solve the problem?

Importing helps in wealthy countries, but it’s not a long-term fix. Supply chains are fragile - disruptions in India or China can trigger global shortages. Many imported drugs don’t meet local regulatory standards. In low- and middle-income countries, import costs are often too high, and logistics are unreliable. The real solution is rebuilding reliable, local manufacturing with government support.

What can regular people do about antibiotic shortages?

You can’t fix the supply chain, but you can help reduce the need for antibiotics. Don’t pressure doctors for antibiotics for colds or flu - they don’t work on viruses. Finish your full course if you’re prescribed them. Support policies that fund antibiotic production and stewardship. And spread awareness: antibiotic shortages aren’t just a hospital problem - they’re a public health emergency.

Adarsh Dubey

December 23, 2025 AT 18:38It’s wild how we treat antibiotics like disposable goods. We’ve got the science to make them, the knowledge to use them wisely, and yet we let market logic decide who lives and who doesn’t. This isn’t a shortage-it’s a choice. And it’s a cruel one.

India produces over 60% of the world’s generic antibiotics, yet our own rural clinics still run out. The disconnect between production and access is staggering. We export lifesavers while our own mothers wait days for amoxicillin.

It’s not about greed alone-it’s about broken incentives. Why would a factory invest in a $0.10 pill when a $10,000 cancer drug gets the same regulatory attention and 100x the profit? We need to decouple antibiotic production from profit motives entirely.

Public manufacturing hubs aren’t radical. They’re basic public health infrastructure, like water treatment plants. We don’t let private companies decide who gets clean water. Why do we let them decide who gets penicillin?

And yes, stewardship matters. But you can’t steward what you don’t have. No amount of responsible prescribing fixes a shelf that’s empty.

This isn’t a ‘healthcare issue.’ It’s a civilizational one. We’re choosing convenience over survival-and our grandchildren will pay the price.

Blow Job

December 25, 2025 AT 11:32I work in a hospital pharmacy in Ohio. Last month, we ran out of amoxicillin for three weeks. Three weeks. Parents were crying in the lobby because their kids couldn’t go to school. We had to give them liquid cephalexin-same thing, kinda, but it tastes like burnt plastic and kids throw it up.

And don’t get me started on the paperwork. Every time we switch meds, we gotta document why, get approval, call the family, explain it’s not ‘better’-just the only thing left. It’s exhausting.

But here’s the thing: we’re not helpless. We’ve started using rapid tests to cut down on unnecessary prescriptions. We’ve cut our broad-spectrum use by almost half. It’s not perfect, but it’s something.

We need government to step in. Not just ‘study it’-actually fund the factories. These aren’t luxury drugs. They’re the foundation of modern medicine. You don’t let the market decide if a kid lives or dies.

Ajay Sangani

December 25, 2025 AT 23:48you know… sometimes i think we’re all just… waiting for the next pandemic to wake us up. like, we’ve known this was coming for 20 years. penicillin shortages since 2015? and still we act like it’s some surprise. maybe its not about money. maybe its about… meaning. we dont value life unless its profitable. we make movies about robots feeling emotions but cant make a pill that saves a child because its ‘not lucrative’

we’re not running out of science. we’re running out of soul. and that’s the real antibiotic shortage.

Pankaj Chaudhary IPS

December 26, 2025 AT 11:59As a public servant who has witnessed the impact of drug shortages firsthand in rural India, I must emphasize that this is not merely a pharmaceutical issue-it is a matter of national security and human dignity.

Our healthcare workers are not magicians. They cannot cure infections without the tools to do so. When a village health center runs out of injectable penicillin, it is not a ‘logistical hiccup’-it is a systemic failure that costs lives.

India must lead by example. We produce 60% of the world’s generic antibiotics. We must ensure that 100% of our own population has access to them before exporting. A national antibiotic reserve, funded and managed by the Ministry of Health, must be established immediately.

Furthermore, we must incentivize domestic production through guaranteed procurement contracts, not subsidies. Companies must know: if you make this drug, we will buy it. No exceptions.

This is not charity. It is justice.

Gray Dedoiko

December 27, 2025 AT 15:57Just read this whole thing. Honestly, I didn’t realize how bad it was. I thought it was just a few drugs missing here and there. But this… this is like the whole system is on fire and we’re all just handing out fans.

I get why companies don’t make them-low profit, high hassle. But if we’re gonna act like we care about public health, we gotta stop pretending market forces are the answer.

Maybe we need to treat antibiotics like vaccines? Government buys, distributes, guarantees supply. No profit motive. Just… life.

Wish more people knew about this. It’s not sexy like AI or crypto, but it’s way more important.

Sidra Khan

December 28, 2025 AT 06:05Okay but like… why are we even still using antibiotics? 🤔 Like, isn’t there some app or AI that can just… fix infections? I saw a TikTok about ‘bacteriophage therapy’ and it looked like sci-fi. Why are we stuck in 1945?

Also, who even uses amoxicillin anymore? Everyone’s on probiotics and lemon water. Maybe we just need to stop being so weak?

Diana Alime

December 30, 2025 AT 00:36So like… I got antibiotics last year for a UTI and it was like $3 at Walmart. How is this a crisis? Are people just bad at budgeting? 😭

Also, why are we always blaming the companies? Maybe doctors are just overprescribing? My cousin’s kid got antibiotics for a cold and now she’s allergic. Maybe we’re the problem??

Also, why are we even talking about this? Can’t we just… fix the economy? Like, if we had more money, we’d buy more drugs, right? 🤷♀️

Jeffrey Frye

December 30, 2025 AT 18:14Let’s be real. This whole ‘antibiotic shortage’ thing is just woke corporate propaganda. Big Pharma doesn’t care. They’re just trying to get more government money. And don’t even get me started on the WHO-they’re a globalist cult.

Also, resistance? That’s just evolution, bro. Maybe the bacteria are smarter than us. Maybe we deserve to get sick.

And why are we even making antibiotics? Why not just let nature take its course? The weak die, the strong survive. That’s how it’s supposed to work.

Also, I heard India’s factories are full of child labor and asbestos. So maybe we should just stop importing. Moral high ground, right?

Also, why is this even a post? Who cares? I got my flu shot. I’m fine.