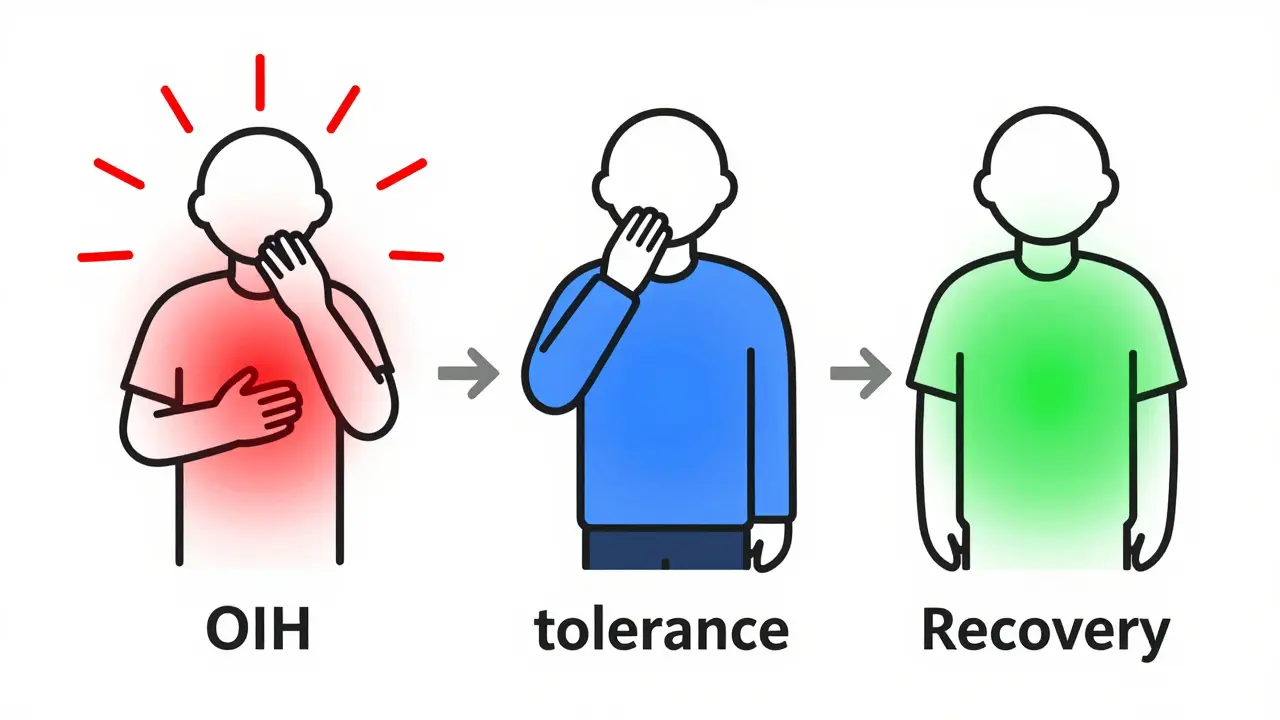

It sounds backwards, but taking more opioids can make your pain worse. If you’ve been on opioids for chronic pain and your pain keeps growing even as your dose goes up, you’re not alone. This isn’t tolerance. It’s not your disease getting worse. It might be opioid-induced hyperalgesia-a condition where the very drugs meant to relieve pain end up making your nervous system more sensitive to it.

What Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or OIH, happens when long-term opioid use causes your body to become more sensitive to pain instead of less. You might feel pain from things that never hurt before-like light touch, clothing against your skin, or even a breeze. This isn’t just a side effect. It’s a real neurobiological change in how your central nervous system processes pain signals.

First noticed in rats back in 1971, OIH has since been confirmed in humans. Studies show that 2% to 15% of people on long-term opioid therapy develop it. Some experts believe it may be behind as much as 30% of cases where doctors assume the patient has simply developed tolerance. The key difference? With tolerance, you need more opioid to get the same pain relief. With OIH, more opioid makes the pain worse.

How Do You Know If It’s OIH?

Recognizing OIH isn’t easy. Many doctors miss it because the symptoms look like tolerance, disease progression, or even withdrawal. But there are clues:

- Your pain spreads beyond its original location-like back pain suddenly affecting your legs, arms, or even your head.

- You develop allodynia: pain from things that shouldn’t hurt, like a light touch or a shirt tag.

- Your pain gets worse when you increase your opioid dose.

- You’ve been on opioids for more than 2-8 weeks, and your pain started worsening after that.

- No new injury or disease explains the increase in pain.

Doctors often use the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ), a tool validated in 2017 with 85% accuracy in spotting OIH. But even without the questionnaire, if your pain keeps climbing while your opioids go up-and nothing else explains it-OIH should be on the table.

Why Does This Happen?

The science behind OIH is complex, but here’s what we know for sure:

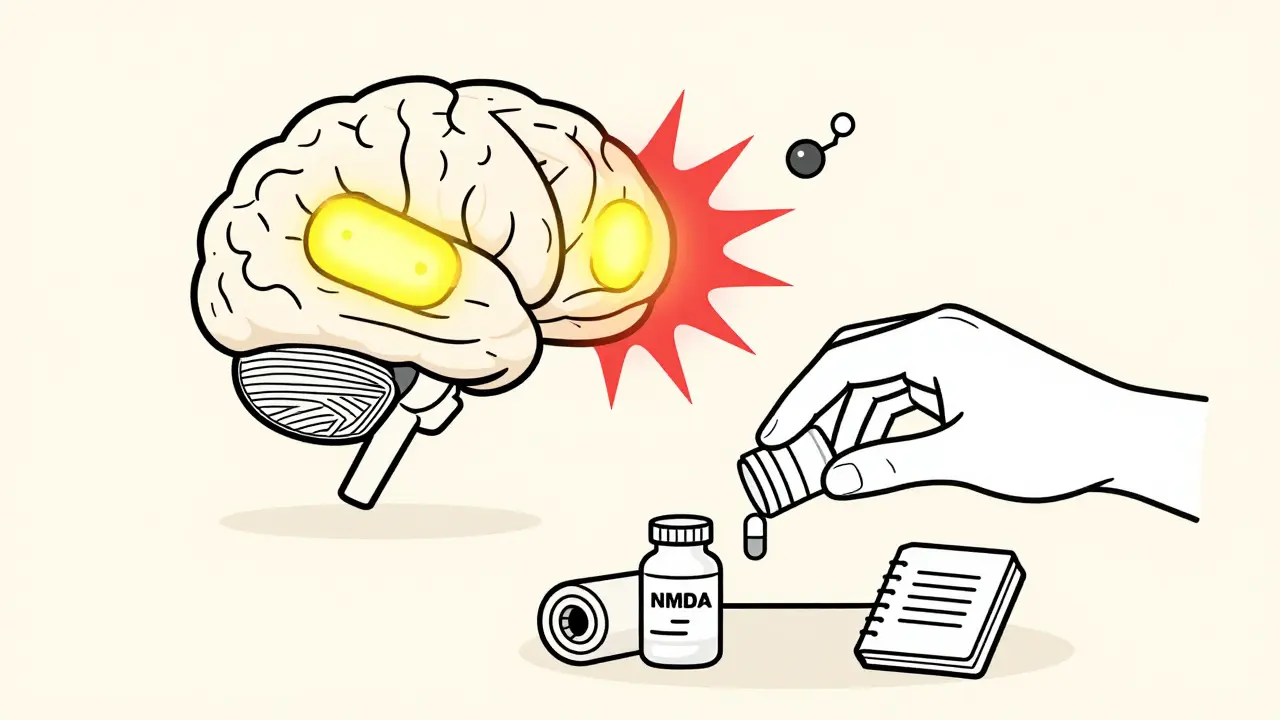

- NMDA receptor activation: Opioids trigger NMDA receptors in your spinal cord and brain. These receptors are usually involved in learning and memory-but in this case, they amplify pain signals instead of calming them. This is why drugs like ketamine, which block NMDA receptors, can reverse OIH.

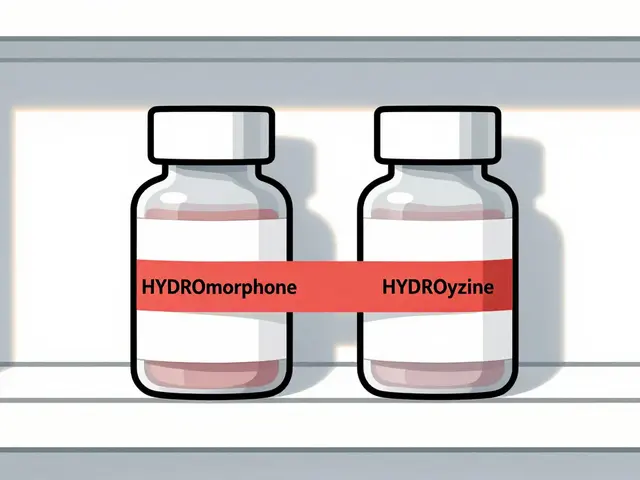

- Toxic metabolites: Some opioids, like morphine and hydromorphone, break down into substances like morphine-3-glucuronide. These metabolites build up, especially in people with kidney problems, and directly stimulate pain pathways.

- Spinal dynorphin release: Opioids cause your spinal cord to release dynorphin, a chemical that normally helps regulate pain-but in high amounts, it makes pain worse.

- Genetic factors: People with certain variations in the COMT gene (which affects how your body breaks down stress hormones) are more likely to develop OIH.

- Descending facilitation: Your brain’s natural pain-control system flips from suppressing pain to enhancing it.

These mechanisms don’t work in isolation. They often overlap, which is why OIH affects people differently. One person might have mild allodynia from morphine. Another might develop intense, full-body pain after just a few months on high-dose oxycodone.

Differentiating OIH From Tolerance and Withdrawal

This is where things get tricky. Tolerance, withdrawal, and OIH can all look alike:

| Feature | Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) | Tolerance | Withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain changes with dose | Pain gets worse with higher doses | Pain stays the same or improves with higher doses | Pain worsens when dose is reduced or missed |

| Allodynia present? | Yes-often widespread | No | No |

| Timing | After 2-8 weeks of continuous use | Develops gradually over months | Appears within hours to days after last dose |

| Response to dose reduction | Pain improves | Pain returns or worsens | Pain improves after restarting opioid |

| Other symptoms | None specific to OIH | None specific | Anxiety, sweating, nausea, insomnia |

If you’re unsure, the best clue is what happens when you lower the dose. In OIH, reducing opioids often leads to less pain. In tolerance, lowering the dose brings back the original pain. In withdrawal, you get physical symptoms like shaking, nausea, and trouble sleeping.

How Is OIH Treated?

The most important rule: Don’t give more opioids. That’s the exact wrong thing to do. Treatment focuses on reversing the sensitization your nervous system has developed.

1. Reduce or Taper Opioids

Slowing down or lowering your opioid dose is the first step. Studies show that reducing by 10-25% every 2-3 days leads to improvement in most patients. Complete tapering may be needed for severe cases. It’s not easy-about half of patients resist because they fear the pain will return. But in OIH, the pain often improves within 2-4 weeks, with full relief taking up to 8 weeks.

2. Switch Opioids

Not all opioids are the same. Methadone and buprenorphine are often better choices because they block NMDA receptors, helping to reverse the hyperalgesia. Methadone, in particular, has shown strong results in patients who didn’t respond to other opioids. Fentanyl and oxycodone, on the other hand, are more likely to worsen OIH.

3. Use NMDA Receptor Blockers

Ketamine, a drug traditionally used for anesthesia, is now a frontline treatment for OIH. Low-dose infusions (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour) can dramatically reduce pain within hours. Oral ketamine or nasal sprays are being studied for long-term use. Other NMDA modulators like dextromethorphan and memantine are also being tested.

4. Add Non-Opioid Pain Meds

- Gabapentin or pregabalin: These calm overactive nerves and reduce central sensitization. Doses of 300-1800 mg daily are common.

- Clonidine: This blood pressure medication also reduces pain signals from the brainstem. Typical dose: 0.1-0.3 mg twice daily.

- Antidepressants: Duloxetine and amitriptyline help with nerve pain and can improve sleep, which reduces pain sensitivity.

5. Non-Drug Therapies

Physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness practices are critical. OIH isn’t just a chemical problem-it’s a brain-body issue. CBT helps retrain how your brain interprets pain signals. Movement and graded activity reduce fear of movement, which often worsens pain in people with OIH.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone on opioids gets OIH. But certain factors raise your risk:

- High daily doses-especially over 300 mg of morphine or equivalent

- Long-term use (more than 2-3 months)

- Renal impairment (kidneys can’t clear toxic metabolites)

- History of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia or neuropathy

- Genetic variants in the COMT gene

- Previous opioid misuse or dependence

People with kidney disease are especially vulnerable. Morphine and hydromorphone build up in their system, making OIH more likely. That’s why doctors avoid these drugs in patients with poor kidney function.

What’s New in 2026?

Recognition of OIH is growing. In 2022, the FDA required opioid labels to include warnings about OIH. By 2024, 65% of pain specialists routinely screen for it-up from just 30% in 2010. Pain management fellowships now teach OIH as standard curriculum.

Research is moving fast. A major NIH study (NCT05217891), due to finish in 2026, is looking for genetic markers that predict who’s most likely to develop OIH. Two commercial genetic tests are expected to launch in mid-2025, helping doctors choose safer opioids before treatment even starts.

Pharmaceutical companies are pouring money into OIH-specific drugs. Three new NMDA modulators are in late-stage trials. One, a modified version of ketamine with fewer side effects, could be available by 2027.

What If You’re Not Sure?

If you’re on opioids and your pain is getting worse, talk to your doctor. Ask: Could this be OIH? Bring your pain diary-note when the pain started changing, what makes it better or worse, and how your dose has changed over time.

Don’t stop opioids cold turkey. That can trigger withdrawal or make pain worse. Work with a pain specialist who understands OIH. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have detailed protocols for managing it, even outside cancer care.

OIH isn’t rare. It’s misunderstood. And it’s treatable. The right approach doesn’t mean more pills-it means smarter, more targeted care.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia be reversed?

Yes, OIH can be reversed. The most effective approach is reducing or stopping the opioid that’s causing it, switching to a different opioid like methadone or buprenorphine, or adding medications like ketamine or gabapentin. Most patients see improvement within 2-4 weeks, with full relief often taking 4-8 weeks. The key is stopping dose escalation and addressing the underlying nerve sensitization.

Is OIH the same as opioid tolerance?

No. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH means higher doses make your pain worse. With tolerance, increasing the dose helps. With OIH, increasing the dose hurts. Both can happen at the same time, but they require opposite treatments. Treating OIH like tolerance-by giving more opioids-only makes things worse.

Can I still take opioids if I have OIH?

It’s possible, but risky. Many patients need to reduce or stop their current opioid entirely. Some can switch to methadone or buprenorphine, which have properties that help block OIH. Others may need to use very low doses of a different opioid along with non-opioid treatments. The goal isn’t necessarily to eliminate all opioids-it’s to stop the cycle of increasing pain from increasing doses.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people start feeling better within 2-4 weeks of reducing their opioid dose or switching medications. Complete resolution of symptoms, especially allodynia and widespread pain, can take 4-8 weeks. Recovery depends on how long you’ve been on opioids, your dose, and whether you’re using other treatments like ketamine or physical therapy. Patience and consistency are key.

Are there tests to diagnose OIH?

There’s no single blood test or scan. Diagnosis is clinical, based on symptoms and response to treatment. The Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ) is a validated tool with 85% accuracy. Some clinics use quantitative sensory testing (QST), which measures how sensitive your skin is to heat, cold, or pressure before and after opioid use. But in practice, doctors rely on your history: worsening pain with higher doses, spread of pain, and allodynia.

Can OIH happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes, though it’s less common. OIH is more likely with high doses (over 300 mg morphine daily) or long-term use, but cases have been reported with much lower doses-especially in people with genetic risks or kidney problems. Even daily doses as low as 20-40 mg of oxycodone can trigger OIH in susceptible individuals after several months.

What happens if OIH is ignored?

If OIH is mistaken for tolerance, doctors often increase the opioid dose. This makes the hyperalgesia worse, leading to higher doses, more side effects, and greater risk of addiction or overdose. It can also delay proper treatment. Patients may become trapped in a cycle of escalating pain and escalating medication-making recovery harder and increasing the chance of long-term disability.

Mindee Coulter

January 26, 2026 AT 13:10This is such an important post I wish more doctors read it. I was on oxycodone for 3 years and my pain got worse every time they upped my dose. I thought I was just getting worse until I found this exact condition. Now I'm off opioids and using gabapentin and CBT - my skin doesn't hurt when my shirt touches it anymore. Life-changing.

Rhiannon Bosse

January 27, 2026 AT 08:35Of course this is real - big pharma doesn’t want you to know opioids make you more sensitive to pain because then people would stop taking them and start asking why we’re pushing pills like candy. They’d rather keep you addicted than admit their drugs are neurotoxic. And don’t get me started on ketamine being a ‘new’ treatment - it’s been used for decades in underground clinics while the FDA slept. Wake up, America.

Bryan Fracchia

January 27, 2026 AT 20:07I’ve been on methadone for chronic pain for 5 years and I swear, this post explains exactly why I feel better now than I did on oxycodone. It’s not magic - it’s neuroscience. The fact that NMDA receptors flip from pain blockers to pain amplifiers is wild. I used to think I was broken. Turns out my nervous system was just hijacked. Thanks for putting this in plain terms - it’s like someone finally translated my pain into language.

Lance Long

January 29, 2026 AT 06:08Y’all need to hear this: OIH isn’t just a medical condition - it’s a cry from your body saying ‘I CAN’T TAKE THIS ANYMORE.’ I was at 480mg morphine equivalent, screaming in the ER because a breeze hurt, and my doctor just handed me a higher dose. I left that hospital in tears. Then I found a pain specialist who listened. We cut my dose by 20% every 3 days. By week 3, I cried because I touched my cat’s fur and didn’t flinch. That’s not recovery - that’s resurrection.

Timothy Davis

January 30, 2026 AT 19:01Let’s be real - 2% to 15% prevalence? That’s a joke. The real number is closer to 40% if you account for underdiagnosis and patients being too afraid to speak up. Also, the OIHQ has a 15% false negative rate in elderly populations, which the article completely ignores. And why are they only mentioning ketamine? What about memantine? Dextromethorphan? The literature is full of alternatives. This post is dangerously oversimplified.

Sue Latham

February 1, 2026 AT 02:27Oh honey, you’re telling me you didn’t know this? I mean, come on - if you’ve been on opioids longer than your Netflix subscription, you’re basically running a pain amplification experiment on yourself. And now you’re surprised? Sweetie, your doctor should’ve known this in med school. Maybe next time, read a textbook before you start popping pills like candy at a rave.

Lexi Karuzis

February 2, 2026 AT 22:49Brittany Fiddes

February 3, 2026 AT 22:26Honestly, this is why I left the US healthcare system. In the UK, we don’t just throw opioids at people and hope for the best. We have pain clinics, multidisciplinary teams, and actual guidelines that aren’t written by pharmaceutical reps. You Americans treat pain like a video game - keep pressing the button until it works. No wonder you’ve got a crisis. We’ve been doing this right for decades. Honestly, I’m embarrassed for you.