When your heart beats, it follows a precise electrical pattern. That pattern shows up on an ECG as a series of waves - P, Q, R, S, and T. The time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave is called the QT interval. If this interval gets too long, it’s called QT prolongation. It doesn’t sound dangerous, but it can be. A prolonged QT interval can trigger a dangerous heart rhythm called torsades de pointes (TdP), which can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. And surprisingly, it’s often caused by medications you’d never suspect.

What Exactly Is QT Prolongation?

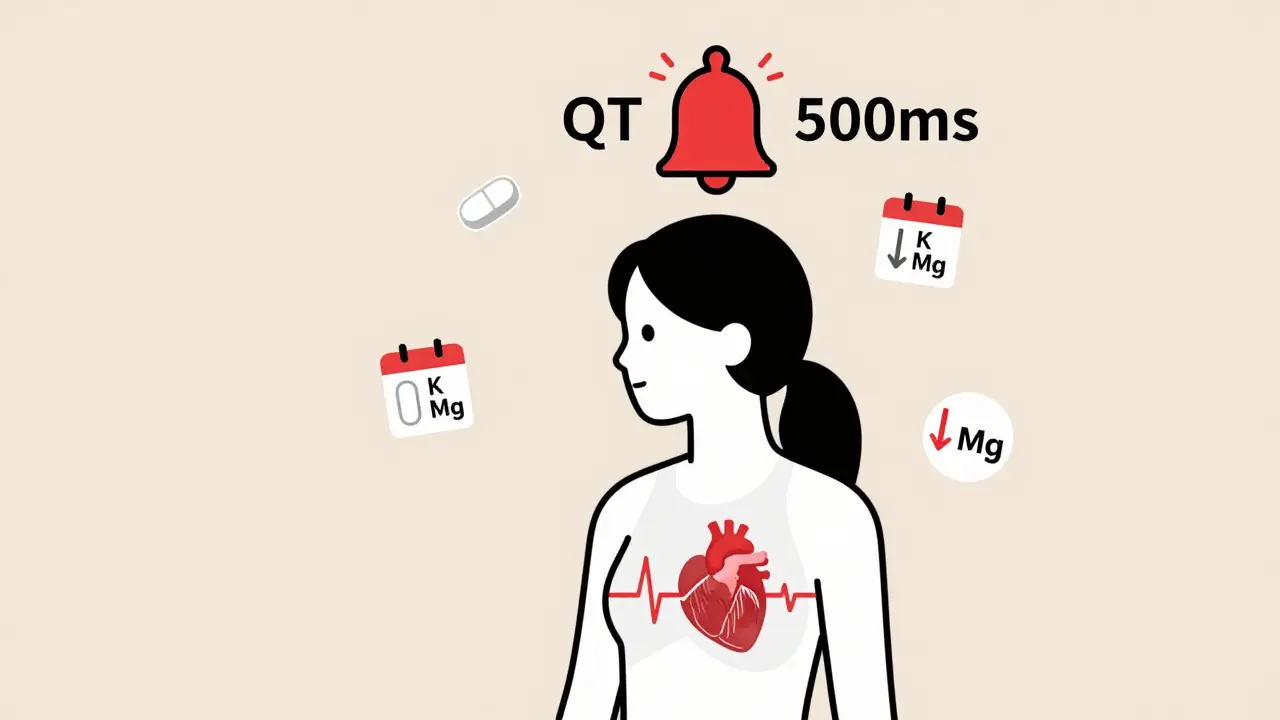

QT prolongation means the heart’s ventricles take longer than normal to recharge after each beat. This delay creates an electrical imbalance. Think of it like a car engine that doesn’t reset properly between cycles - it sputters, stalls, or worse. The most common cause isn’t genetics; it’s drugs. When certain medications block the hERG potassium channel - a key player in resetting the heart’s electrical system - the repolarization phase stretches out. That’s what stretches the QT interval on the ECG. The standard way to measure this is the corrected QT interval, or QTc. It adjusts for heart rate because a faster heart rate naturally shortens the QT interval. The most common formula used is Bazett’s, but it’s not perfect. At very slow or very fast heart rates, it can mislead. Still, doctors rely on it. A QTc over 500 milliseconds is a red flag. An increase of more than 60 ms from your baseline is also concerning - even if it doesn’t hit 500.Drugs That Can Trigger QT Prolongation

Not all drugs that prolong QT are heart medications. In fact, many are everyday prescriptions. The U.S. FDA identified 46 out of 205 tested drugs as confirmed QT prolongers. By 2018, crediblemeds.org listed 223 drugs with known, possible, or conditional risk. Here’s how they break down:- Class Ia antiarrhythmics: Quinidine and procainamide. These were among the first drugs linked to TdP. Quinidine causes TdP in about 6% of users.

- Class III antiarrhythmics: Sotalol, dofetilide, ibutilide. These are designed to prolong repolarization to stop arrhythmias - but they can cause them instead. Sotalol has a 2-5% risk of TdP. Amiodarone also prolongs QT, but its risk is lower (0.7-3%) because it blocks multiple channels, not just hERG.

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin and clarithromycin (macrolides) can prolong QT by 15-25 ms. Even azithromycin, often considered safer, has been tied to cases. Moxifloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) adds 6-10 ms on average.

- Antifungals: Fluconazole, especially at higher doses, increases risk.

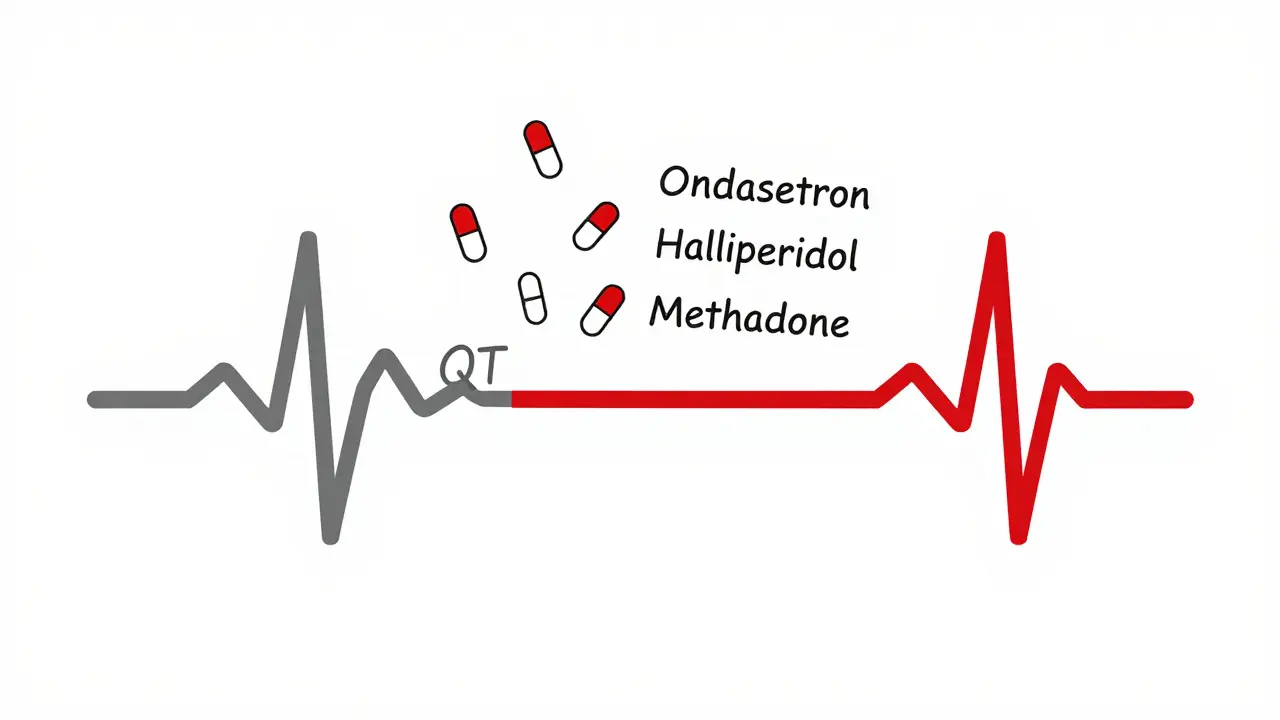

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol and ziprasidone carry black box warnings for arrhythmias. Ziprasidone’s risk is high enough that the FDA requires it to carry a warning about sudden death.

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (Zofran) is widely used for nausea, especially after chemo or surgery. But it’s one of the most common culprits in TdP cases. In one study, 42% of reported TdP cases involved ondansetron.

- Antidepressants: Citalopram and escitalopram (SSRIs) show dose-dependent QT prolongation. The FDA capped citalopram at 40 mg/day (20 mg if over 60) because of this.

- Opioid replacement: Methadone is a major offender. Doses over 100 mg daily significantly raise TdP risk. Many patients on long-term methadone maintenance have QTc values over 470 ms - but with careful monitoring, serious events are rare.

- Newer drugs: Cancer drugs like vandetanib and nilotinib, and even new weight-loss drugs like retatrutide (approved in late 2023), now carry QT prolongation warnings.

Why Do Some People Get TdP and Others Don’t?

It’s not just the drug. It’s the combination. A 2020 review of 147 TdP cases found that 68% involved two or more QT-prolonging drugs. A single drug might be low-risk. Two? The risk multiplies. For example, combining ondansetron with haloperidol - a common pairing in emergency rooms for nausea and agitation - creates a perfect storm. Women are at higher risk. About 70% of documented TdP cases occur in women. Why? Hormones. Estrogen slows down the heart’s repolarization. That’s why postpartum women are especially vulnerable. Age matters too. Older adults often have reduced kidney or liver function, leading to higher drug levels. Electrolyte imbalances - low potassium, low magnesium - make things worse. And genetics play a role. About 30% of drug-induced TdP cases involve inherited variants in the hERG gene or related channels.

How Do Doctors Spot and Manage the Risk?

The European Society of Cardiology recommends a baseline ECG before starting high-risk drugs. Repeat it within 3-7 days, especially after a dose increase. That’s not optional for drugs like sotalol or methadone. In Australia, many hospitals now use automated alerts in their electronic health records. If a pharmacist tries to prescribe ondansetron to someone already on haloperidol and azithromycin, the system flags it. One study showed that hospitals with integrated decision support tools cut inappropriate prescribing by 58%. But tools aren’t perfect. Many clinicians still struggle with interpreting QTc correctly - especially when the heart rate is under 50 or over 90. And some drugs have long half-lives. Amiodarone can stick around for weeks. So an ECG done a day after starting it might miss the peak effect. Medsafe (New Zealand’s drug safety authority) says: if QTc exceeds 500 ms or increases more than 60 ms from baseline, stop the drug - unless there’s a life-threatening reason to keep it. That’s a clear, practical rule. But in practice, it’s not always followed. A 2022 survey of 327 pharmacists found that 63% found it hard to judge safe combinations, especially with newer oncology drugs.What’s Changing in Drug Safety Testing?

For years, regulators focused only on QT interval changes. But that’s outdated. The Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) initiative, launched in 2013, changed everything. Now, drug developers must test how a compound affects multiple ion channels - not just hERG - and use computer models to predict arrhythmia risk. Since 2016, 22 drugs have been dropped from development because of proarrhythmia risk flagged by CiPA. Each failure costs an average of $2.6 billion. The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance makes CiPA mandatory for all new drug applications starting January 2025. That means fewer risky drugs will hit the market. But it also means existing drugs - especially older ones - aren’t held to the same standard. That’s why databases like crediblemeds.org are so vital. They’re updated quarterly and list drugs by risk level: Known Risk, Possible Risk, and Conditional Risk.

Real-World Stories: When Things Go Wrong - and Right

One emergency room physician in Brisbane described a 65-year-old woman who came in with vomiting and diarrhea. She was given ondansetron and azithromycin - standard treatment. Within 24 hours, her QTc jumped from 440 ms to 530 ms. She went into TdP. She survived, but barely. Her case wasn’t rare. It’s textbook. On the other hand, a 2021 study tracked 87 patients on methadone for opioid use disorder. Their QTc values went as high as 490 ms. But with monthly ECGs, magnesium supplements, and dose limits, not a single case of TdP occurred. That’s proof that risk can be managed - if you’re paying attention.What Should You Do?

If you’re on any of these drugs - especially more than one - ask your doctor:- Has my QT interval been checked recently?

- Am I on any other meds that could interact?

- Do I have low potassium or magnesium?

- Is there a safer alternative?

Future Outlook

Artificial intelligence is starting to help. A 2024 study trained an AI to analyze ECG waveforms beyond just measuring QT. It predicted TdP risk with 89% accuracy by spotting subtle changes in T-wave shape and amplitude - things even experienced cardiologists miss. That’s promising. Genetic testing is also improving. Researchers identified 23 genetic variants that explain 18% of why some people are more susceptible. In five years, we might screen for these before prescribing. For now, the best defense is awareness. Know your meds. Know your risk. And if something feels off - get an ECG.What is the QT interval, and why does it matter?

The QT interval is the time on an ECG from the start of the Q wave to the end of the T wave. It represents how long the heart’s lower chambers take to electrically recharge. If it’s too long, the heart can develop a dangerous rhythm called torsades de pointes, which may lead to sudden cardiac arrest. A corrected QT interval (QTc) over 500 ms or an increase of more than 60 ms from baseline is considered high risk.

Which medications are most likely to cause QT prolongation?

High-risk medications include quinidine, sotalol, dofetilide, and amiodarone (antiarrhythmics); erythromycin and azithromycin (antibiotics); haloperidol and ziprasidone (antipsychotics); ondansetron (anti-nausea); citalopram (antidepressant); and methadone (opioid treatment). Even newer drugs like retatrutide and certain cancer therapies now carry warnings. The risk increases when multiple drugs are taken together.

Can QT prolongation be reversed?

Yes, in most cases. Stopping the offending drug often allows the QT interval to return to normal within days. Correcting low potassium or magnesium levels helps too. In severe cases, doctors may give intravenous magnesium sulfate to stabilize the heart rhythm. Long-term damage is rare if caught early.

Why are women at higher risk for drug-induced TdP?

Women naturally have longer QT intervals than men due to hormonal differences, especially estrogen. This makes their hearts more sensitive to drugs that delay repolarization. About 70% of documented TdP cases occur in women, and risk increases further after childbirth or during menopause.

Should everyone get an ECG before taking a new medication?

No - but you should if you’re taking a high-risk drug, are over 65, female, have heart disease, kidney problems, or are on multiple medications that affect the heart. For low-risk drugs, universal screening isn’t cost-effective. But for high-risk combinations, an ECG before and within a week of starting is strongly recommended by guidelines.

How can I check if my medication is on the risk list?

Visit crediblemeds.org, a free, publicly accessible database updated quarterly. It lists drugs by risk level: Known Risk, Possible Risk, and Conditional Risk. You can search by drug name. Many hospitals and pharmacies now integrate this data into their prescribing systems to warn clinicians.

Chima Ifeanyi

February 7, 2026 AT 08:38Let's cut through the noise: QT prolongation isn't some mysterious medical anomaly-it's a pharmacokinetic inevitability when you throw hERG blockers into a polypharmacy soup. The FDA's 46-drug list is a joke. CredibleMeds has 223 because they're not filtering for clinical relevance. You're telling me azithromycin's 15ms prolongation is equivalent to quinidine's 80ms? That's not risk stratification, that's fearmongering. And don't get me started on Bazett's formula-heart rate correction is a statistical illusion at extremes. A 40-year-old athlete with HR 45 and QTc 490 is not at the same risk as a 72-year-old with HR 85 and QTc 495. The entire paradigm is built on flawed math and regulatory overreach.

Elan Ricarte

February 8, 2026 AT 07:39Oh wow, another ‘awareness’ piece. Let me guess-next you’ll be telling us to ‘ask our doctor’ like that’s some magical incantation. Newsflash: your doctor’s EHR doesn’t even warn them about combo risks unless it’s a felony. I’ve seen a guy on methadone, ondansetron, and citalopram get discharged with ‘no concerns.’ And now we’re supposed to be grateful because AI can ‘predict TdP with 89% accuracy’? That’s not prevention, that’s damage control with a fancy name. They’re not fixing the system-they’re just making better coffins. And retatrutide? The same pharma giants who sold us opioids are now selling us weight-loss drugs that could kill you if you’re female and over 60. Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s profit with a stethoscope.

Angie Datuin

February 9, 2026 AT 06:02Thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’m a nurse and I see this all the time-patients on 3-4 meds, no one checking QTc. It’s scary how many providers still think ‘it’s just a number.’ But you’re right: it’s not about scaring people, it’s about empowering them. I always tell my patients: if you’re on more than one of these, ask for a baseline ECG. It takes 5 minutes. Could save your life. No shame in asking.

glenn mendoza

February 9, 2026 AT 12:51Thank you for this meticulously researched and profoundly important exposition. The clinical implications of QT prolongation are not merely theoretical-they are life-or-death realities that demand our collective vigilance. The confluence of pharmacological, physiological, and demographic risk factors-particularly in postmenopausal women and those with renal impairment-cannot be overstated. It is both a moral and professional imperative that clinicians prioritize baseline and serial ECG monitoring, especially when polypharmacy is involved. The emergence of CiPA represents not merely a technological advancement, but a paradigmatic shift toward patient-centered safety. Let us not rest until every prescribing decision is informed by the full spectrum of electrophysiological risk.

Ritteka Goyal

February 9, 2026 AT 18:15OMG this is sooo true!! I read this and I was like, wow, India is so behind in this!! In India we just give ondansetron for vomiting like it’s candy!! My cousin got TdP after getting Zofran + azithromycin + her blood pressure med!! She was in ICU for 3 days!! And no one even checked her ECG!! Why do you think they don’t test here?? Because pharma companies don’t care about poor countries!! We need to boycott all these drugs!! And also, why is everyone talking about women?? What about men?? Men get heart problems too!! I think the real problem is that doctors are lazy and don’t wanna do ECGs!! We need to make it mandatory!! Like, if you prescribe any of these, you gotta do ECG first!! Or you go to jail!!

Ashlyn Ellison

February 10, 2026 AT 19:46My grandma’s on methadone and they never checked her QT. She’s 71, female, on 5 meds. I’m getting her an ECG next week. Just because you’re not symptomatic doesn’t mean you’re safe. This post scared me into action.

Jonah Mann

February 12, 2026 AT 11:54Wait wait wait-so you’re saying azithromycin causes QT prolongation? I thought that was just erythromycin?? I read somewhere that azithro’s safe? But then again I saw a tweet that said the FDA added it to the list in 2020? I’m confused. Also, is it true that magnesium helps? I’ve been taking 400mg daily. Should I up it? And what about potassium? I eat bananas but maybe I need a supplement? My doc says I’m fine but I’m not sure anymore. Also, my cousin’s on ziprasidone and she says she feels weird sometimes. Should she get an ECG? I’m kinda panicking now. I need a flowchart.

THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI

February 13, 2026 AT 23:01Bro this is gold. I work in a hospital in Kerala and we see this every week. Patients come with fever, get antibiotics, then get ondansetron for nausea, then get antipsychotic for agitation. No ECG. No labs. Just vibes. We need to push for mandatory QT screening for all polypharmacy patients over 50. Also, why is no one talking about Ayurvedic herbs? I’ve seen people on ashwagandha + guggul + cardiac meds and their QT goes wild. No one tests for that. Pharma companies don’t care about herbal interactions. We need a database for traditional meds too. I’m starting a petition. Join me?

MANI V

February 14, 2026 AT 05:00How can you even write this without mentioning that the entire QT paradigm was created by Big Pharma to sell more ECG machines and force unnecessary testing? They profit from fear. The ‘risk’ of TdP is exaggerated. Most cases are from people who already had underlying heart disease. They’re blaming the drugs, not the patients. And don’t get me started on the gender bias-women aren’t ‘more sensitive,’ they’re just more likely to be prescribed these drugs because doctors think they’re ‘emotional’ and need anti-nausea meds. This isn’t science. It’s institutionalized sexism with a lab coat.

Susan Kwan

February 14, 2026 AT 19:46Wow. A 40% failure rate among cardiologists checking QTc before prescribing sotalol? And you’re surprised? This isn’t a medical issue-it’s a cultural one. We’ve turned medicine into a checklist sport. ‘Did you document the QT?’ ‘Did you flag the drug?’ ‘Did you update the EHR?’ But did you actually look at the patient? Did you ask if they’re taking that new ‘natural’ supplement? Did you consider their sleep, stress, or caffeine? No. Because it’s easier to blame the drug than to admit we’re overworked and undertrained. So yes, get an ECG. But also, demand better training. Demand better systems. And demand that your doctor stop treating you like a data point.

Random Guy

February 16, 2026 AT 11:31So… let me get this straight. If I take Zofran after chemo, and my doc prescribes azithromycin for a cough, and I’m a woman over 60… I’m basically a walking time bomb? And the only way to survive is to get an ECG every time I get sick? And if I can’t afford it? Too bad? And they’re gonna put AI in charge now? Like, ‘Hey Siri, is my T-wave gonna kill me today?’ This is the future? I thought we were supposed to be curing cancer, not just predicting when we’ll drop dead from a nausea pill.

Ryan Vargas

February 18, 2026 AT 09:18Consider the implications: QT prolongation isn’t a physiological anomaly-it’s a symptom of a deeper systemic collapse. The hERG channel is not merely a biological mechanism; it is a symbolic vessel through which corporate capitalism exerts control over the human body. By reducing cardiac function to a measurable interval, medicine has surrendered its soul to quantification. The FDA’s reliance on Bazett’s formula is not a scientific choice-it’s a metaphysical surrender to the illusion of precision. We are not treating arrhythmias. We are appeasing algorithms. And the real tragedy? The patients who die are not victims of drugs. They are victims of a system that refuses to see them as whole beings, only as data streams. The solution is not more ECGs. It is the dismantling of the entire paradigm of reductionist pharmacology.

Camille Hall

February 18, 2026 AT 18:52I really appreciate how you broke this down. As someone who works with elderly patients on multiple meds, I’ve seen too many close calls. The key isn’t just knowing the drugs-it’s knowing the person. A 68-year-old woman on methadone, with low potassium and a history of GI issues, needs a different approach than a 30-year-old man on one antibiotic. We need to stop treating this like a checklist and start treating it like a relationship. And yes-magnesium and potassium matter. So does sleep. So does hydration. So does listening. If you’re worried, ask. If you’re unsure, get an ECG. It’s not paranoia. It’s self-care.

glenn mendoza

February 18, 2026 AT 19:22While I appreciate the depth of analysis presented, I must respectfully challenge the assertion that QT prolongation is primarily a pharmacological phenomenon. The literature consistently demonstrates that electrolyte disturbances, particularly hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, are not merely contributing factors-they are often the primary precipitants in clinically significant TdP events. The emphasis on medication lists, while necessary, inadvertently shifts focus away from foundational physiological support. In clinical practice, correcting serum potassium to >4.0 mmol/L and magnesium to >2.0 mg/dL often normalizes the QTc independently of drug discontinuation. This underscores the necessity of routine electrolyte monitoring in all patients prescribed QT-prolonging agents, regardless of baseline cardiac history. The integration of electrolyte assessment into prescribing protocols may yield greater risk reduction than even the most sophisticated decision-support systems.