On December 25, 1956, a baby was born in Germany with arms and legs that looked like flippers-limbs that hadn’t fully formed. No one knew why. That baby was the first of more than 10,000 children worldwide who would be born with devastating deformities, all because their mothers took a pill meant to ease morning sickness. The drug was thalidomide, and it became the most infamous teratogenic medication in history.

What Is a Teratogenic Drug?

A teratogenic drug is one that causes birth defects when taken during pregnancy. These aren’t just minor issues-they’re structural changes to the developing fetus that can affect limbs, organs, the brain, and more. The critical window for damage is narrow: between the 34th and 49th day after the mother’s last period. That’s just five to seven weeks into pregnancy, often before a woman even knows she’s pregnant.

Before thalidomide, most doctors assumed that if a drug was safe for adults, it was safe for unborn babies. That belief was wrong. The placenta doesn’t block everything. Some chemicals slip right through-and thalidomide was one of them.

The Rise and Fall of Thalidomide

Thalidomide was invented in 1954 by a German pharmaceutical company, Chemie Grünenthal. It was marketed as a safe sedative and anti-nausea pill. Unlike other drugs at the time, it wasn’t addictive and didn’t cause drowsiness in the morning. It became a household name in over 46 countries. Pregnant women took it by the millions. In Germany, it was called Contergan. In the UK, it was Distaval. In Canada, it was Kevadon.

But something strange was happening. Babies were being born with missing or shortened limbs-phocomelia. Some had no arms at all. Others had hands attached directly to their shoulders. Some were born without ears, eyes, or internal organs. Others had heart defects or spinal cord damage.

Two doctors, independently, connected the dots. In Australia, Dr. William McBride noticed a spike in these rare birth defects in his clinic. He wrote a letter to The Lancet in June 1961, suggesting thalidomide was the cause. In Germany, Dr. Widukind Lenz had been collecting cases and noticed the same pattern. On November 15, 1961, he called Grünenthal and warned them. By November 27, the drug was pulled from the German market. The UK followed on December 2. The U.S. never approved it widely-thanks to Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey at the FDA, who refused to sign off because the safety data was incomplete. Her refusal saved thousands of American babies.

The Scope of the Disaster

Between 10,000 and 20,000 children were born with thalidomide-related defects. Around 40% died before their first birthday. Survivors faced lifelong disabilities. Many couldn’t walk, feed themselves, or hold objects. Some needed prosthetics. Others required multiple surgeries. The damage wasn’t just physical. Families were shattered. Parents were blamed. Society didn’t know how to respond.

A 1964 UK government report found that thalidomide could damage almost every organ system: the esophagus, heart, gallbladder, appendix, even the eyes. It wasn’t just limbs-it was everything. And it didn’t take much. One dose during the critical window was enough to cause irreversible harm.

Why Wasn’t It Caught Sooner?

Drug testing in the 1950s was minimal. Animal tests were done, but mostly on adult animals-not pregnant ones. The idea that a drug could harm a fetus wasn’t seriously considered. Scientists didn’t know how to test for teratogenicity. Even when McBride asked for animal studies, his request was denied by university pharmacologists. The medical community didn’t believe a drug could selectively harm a developing embryo while leaving the mother unharmed.

Also, the timing was tricky. Birth defects showed up months after exposure. Doctors didn’t think to ask mothers about medications taken weeks before birth. By the time the pattern emerged, it was too late for most.

Thalidomide’s Unexpected Comeback

In 1964, Dr. Jacob Sheskin, a doctor in Israel, gave thalidomide to a leprosy patient suffering from painful skin sores. The sores disappeared. He published his findings. It turned out thalidomide was powerful against inflammation and immune reactions.

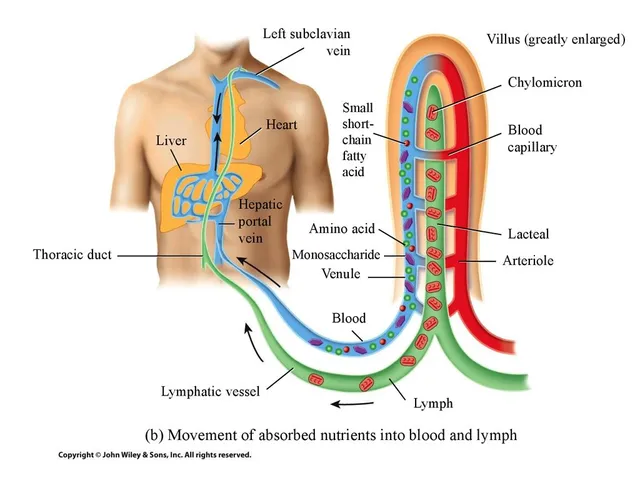

By the 1980s, researchers discovered why: thalidomide blocks angiogenesis-the growth of new blood vessels. Tumors need blood vessels to grow. So did developing limbs. That’s why it caused birth defects. And that’s why it could fight cancer.

In 1998, the FDA approved thalidomide for erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a complication of leprosy. In 2006, it was approved for multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer. Clinical trials showed it improved survival rates. At three years, patients on thalidomide had a 42% progression-free survival rate compared to 23% without it. Overall survival jumped from 75% to 86%.

But the side effects were brutal. Up to 60% of patients developed severe nerve damage-numbness, tingling, burning pain in hands and feet. Many had to stop taking it.

Modern Use: Strict Rules, No Exceptions

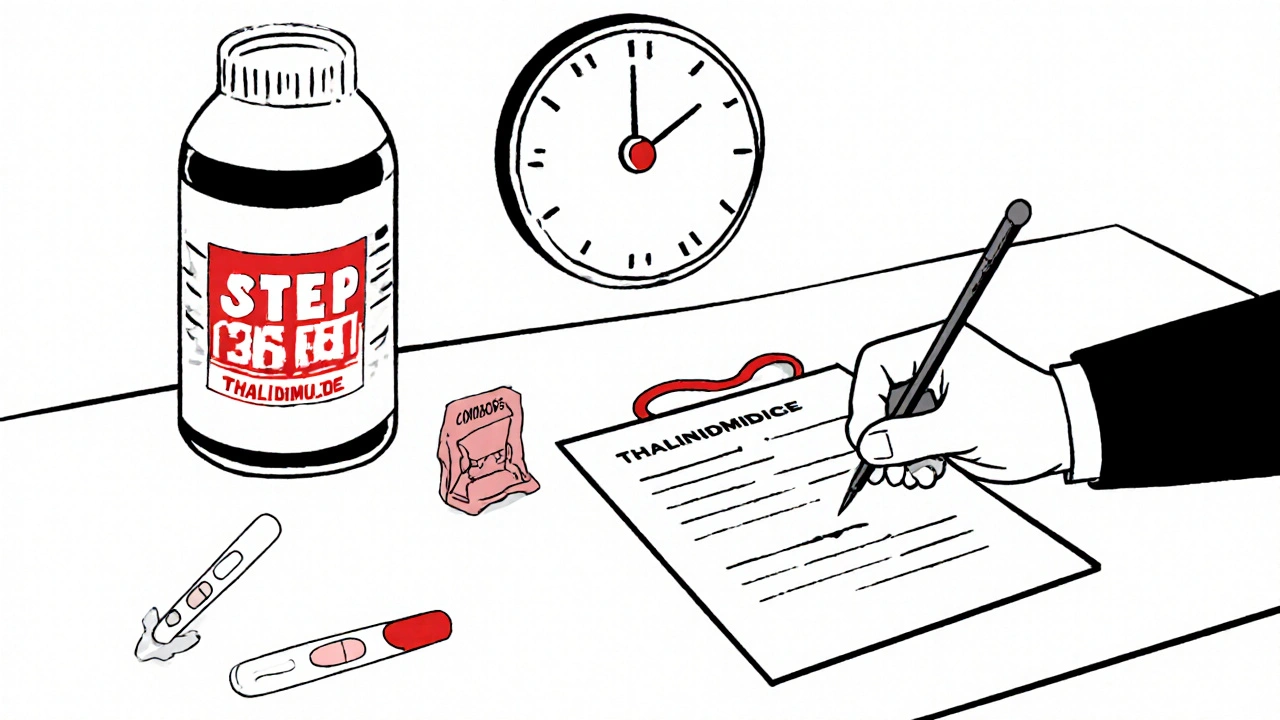

Today, thalidomide is still used-but under the tightest controls in medical history. The U.S. runs the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS). Here’s what it requires:

- Women of childbearing age must have two negative pregnancy tests before starting the drug.

- They must use two forms of birth control simultaneously.

- They must sign a consent form acknowledging the risks.

- They must get monthly pregnancy tests while on the drug.

- Men taking thalidomide must use condoms-because the drug can be present in semen.

- Prescriptions are limited to 28 days at a time.

Pharmacies can’t dispense it without verifying all steps are completed. The drug is so dangerous that even a single missed dose of birth control can be life-altering for a future child.

The Legacy: How Thalidomide Changed Medicine

Thalidomide didn’t just kill babies. It changed how drugs are made, tested, and approved.

In 1962, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. Now, every new drug must prove both safety and effectiveness before it can be sold. Manufacturers must test for teratogenicity using pregnant animals. They must report side effects in real time. Clinical trials must include women of childbearing age-and study the effects on fetuses.

Similar laws spread across Europe, Canada, Australia, and beyond. The UK created the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in 1963. Other countries followed.

Today, every drug label includes pregnancy risk categories. Pharmacists check for interactions. Doctors ask: "Are you pregnant? Could you be?"

What We Learned

Thalidomide taught us that safety isn’t assumed-it’s proven. That a drug can be both a miracle and a monster. That the same molecule that kills cancer cells can also stop a baby’s limbs from growing.

It showed us that science doesn’t always move fast enough. That regulators can be too trusting. That patients need more than promises-they need proof.

And it taught us that sometimes, the same science that causes harm can also heal-if we’re careful enough.

Today, thalidomide still saves lives. But it’s never given lightly. Every bottle carries a warning. Every prescription is tracked. Every patient is educated. And every doctor knows: what happened in the 1950s must never happen again.

That’s the real lesson. Not just that thalidomide is dangerous. But that medicine, when unchecked, can be deadly. And that vigilance, not trust, is the foundation of safe care.

Bailey Sheppard

November 18, 2025 AT 08:10It's wild how one drug could change medicine forever. I never realized how little we knew about fetal development back then. The fact that doctors didn't test on pregnant animals is almost unthinkable now.

Kristi Joy

November 18, 2025 AT 09:16Dr. Kelsey’s refusal to approve thalidomide is one of the quietest acts of heroism in medical history. She stood alone against pressure, bureaucracy, and corporate lobbying-just because she asked for better data. That’s the kind of integrity we need more of today.

Hal Nicholas

November 18, 2025 AT 22:10Let’s be real-this whole thing was avoidable. If the pharmaceutical companies had cared more about profits than headlines, they’d have done basic tests. But no, they wanted a miracle pill for morning sickness and didn’t care who got hurt.

Louie Amour

November 18, 2025 AT 22:26Anyone who still thinks drug regulation is overblown needs to read this. The fact that we’re even debating this in 2025 shows how little we’ve learned. Thalidomide wasn’t an accident-it was negligence dressed up as innovation.

Kristina Williams

November 20, 2025 AT 18:27They knew. They always knew. The government, the drug companies-they buried the data because they were scared of losing money. And now they’re using it again? That’s not science, that’s a cover-up with a prescription pad.

Sarah Frey

November 21, 2025 AT 02:23The STEPS program is one of the most rigorous drug safety protocols ever implemented. It reflects a hard-won understanding: trust must be earned through structure, not assumed through reputation. Every requirement-two forms of contraception, monthly testing, male condom use-is a direct response to a failure that cost thousands of lives.

Girish Pai

November 22, 2025 AT 23:57India’s pharma industry didn’t produce thalidomide, but we learned from it. Our regulatory framework now includes mandatory teratogenicity screening for all new chemical entities. The global standard? Still catching up. We didn’t wait for a tragedy to act-we watched, adapted, and improved.

Shilpi Tiwari

November 23, 2025 AT 06:08Angiogenesis inhibition is the key mechanism here-thalidomide’s teratogenicity and anticancer activity are two sides of the same molecular coin. The drug interferes with VEGF signaling pathways during embryogenesis, disrupting limb bud vasculature. In tumors, it starves neovascularization. Same pathway. Opposite outcomes. Elegant, tragic, and profoundly instructive.

Christine Eslinger

November 24, 2025 AT 16:22It’s not just about the drug-it’s about how we treat vulnerability. Pregnant women weren’t seen as patients with unique needs; they were an afterthought. Today, we still underestimate how much medical research excludes women and developing life. Thalidomide didn’t just expose bad science-it exposed our moral blind spots.

We don’t need more drugs. We need more humility.

Denny Sucipto

November 25, 2025 AT 20:19I used to think medicine was all about fixing things. Now I know it’s just as much about not breaking them. That little pill didn’t just hurt babies-it hurt trust. And we’re still trying to rebuild that.

Holly Powell

November 26, 2025 AT 16:26The STEPS protocol is performative safety theater. Real prevention would require eliminating thalidomide entirely. The fact that we’re still prescribing it under ‘strict controls’ proves our system is designed to rationalize risk, not eliminate it.

Emanuel Jalba

November 27, 2025 AT 14:28😭 This is why I can't trust big pharma. They kill babies, then make billions off the same drug with a fancy label. And they still get to give speeches about 'medical progress.' I'm done.

Heidi R

November 28, 2025 AT 15:58They’re using it again. That’s all you need to know.

Brenda Kuter

November 30, 2025 AT 11:21They’re testing it on pregnant animals now? What took them so long? And why are we still letting anyone near this poison? It’s not medicine-it’s a time bomb in a pill bottle.